| layout | title | description | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

default |

A STUDY IN WHOLE-BODY VIBRATION IN MILITARY ARMORED VEHICLES AND THE IMPACT IT HAS ON HUMAN RESPONSE TIME AND OTHER HUMAN FACTORS |

whole-body vibration, military, iPod touch, consumer electronics, response time, lower back pain, vehicle rollover |

A STUDY IN WHOLE-BODY VIBRATION IN MILITARY ARMORED VEHICLES AND THE IMPACT IT HAS ON HUMAN RESPONSE TIME AND OTHER HUMAN FACTORS

Keywords: whole-body vibration, military, iPod touch, consumer electronics, response time, lower back pain, vehicle rollover

ABSTRACT

The 91st Missile Wing drove approximately 4 million miles last year on U.S. highways and gravel roads in North Dakota (Pape, 2016). This study focused on the UA-HMMWV (Up Armored-High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle). Military security forces (SF) that operate these vehicles suffered from a high rate of lower back pain and vehicle rollover. These rollover accidents are especially common in the HMMWV when driving on gravel roads. This study focused on whole-body vibration (WBV) and its human health and performance effects in relation to driving armored vehicles. Acceleration data was measured using an iPod Touch that was outfitted with an application that measured WBV. An iPad Mini was used to measure reaction time. A survey was conducted to determine discomfort and back pain. The study postulated that as the WBVs in an armored vehicle increase then there will be a significant increase in back discomfort and pain in armored vehicle operators. This study also suggested that there is a positive dose-response correlation between the length and magnitude of exposure to WBV and response-time in an armored vehicle. Nine of the eighteen vibration dose values were within the Health Guidance Caution Zone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to express my full thanks to all parties that have played a part in this study. To include my wife, Chelsea for always being at my side and willing to sacrifice in order to pursue an advanced education. I am very thankful to Dr. Blyukher, Dr. Sheldon, Lt Col Nelson, and the Airman of the 91st Security Forces Group. This project would not have been possible without the flexibility and dedication of the Minot AFB leadership and team. They have provided a wealth of mentorship, support, and guidance through authoring this project.

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have found that continual exposure to WBV will increase lower back pain and health problems of workers (Zengyong Li et al., 2012; Arslan, 2014). At Minot Air Force Base, (MAFB) there are many remote underground Launch Facilities (LFs) that are defended around the clock by military security forces (SF). The LFs house one of the nation’s most powerful weapon systems; The Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Airman of the U.S. military are tasked with driving heavy armored vehicles on often unruly and uneven gravel roads. The primary goal of this project was to quantify the relationship of WBV, response time, and lower back pain using consumer electronics.

Statement of the Problem

The 91st Missile Wing drive approximately 4 million miles per year in the missile complex which is roughly the size of New Jersey (Pape, 2016). The fleet includes a wide variety of vehicles; but, the UA-HMMWV (Up Armored-High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle), is used to provide security and is critical to mission success. Military SF suffer from a high rate of lower back pain and vehicle rollover. These rollover accidents are especially common in the Humvee when driving on gravel roads.

Purpose of the Study

To a large extent, the purpose of this study was to shed light on the effect of WBV in military SF. It is common for accident investigation reports to attribute delayed response as the primary contributor of an accident. This study adds to the body of knowledge focused on the human health effects of WBV. This study adds data to a small pool of WBV measurements in vehicles. It is also one of the first studies of its kind to focus specifically on armored vehicles.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Null Hypothesis:

I. There is no statistically significant correlation between reported lower back pain and whole-body vibration dose in an armored vehicle.

II. There is no statistically significant correlation between the dose of whole-body vibration and response-time in an armored vehicle.

Alternative Hypotheses:

I. There is a statistically significant correlation between reported lower back pain and whole-body vibration dose in an armored vehicle.

II. There is a statistically significant correlation between the dose of whole-body vibration and response-time in an armored vehicle.

Significance of the Study

Through this studies data collection, the author accomplished a greater understanding of the human health hazard that WBV poses to professional drivers. Firstly, this study recommends updates to seating and chair equipment in future armored vehicles. Secondly, the data collected can be used to support future road improvement projects in North Dakota. If the gravel roads can be minimized, then the duration and magnitude of exposure would be reduced or even eliminated. It was thought there could be a positive relationship between the amount of vibration experienced and reaction time. This could be explained by ultimately an increase in the risk of a rolled vehicle accident. WBV exposure is therefore a possible leading safety performance indicator in the operation and health of armored vehicle operators. This study provides valuable insight for military leaders that may not have weighed the risks that WBV pose to traveling personnel.

Limitations and Delimitations of the Study

Limitations:

This study was limited in the areas of: resources, equipment, and the author’s own personal experience with quantitative data collection. The main resource that would be ideal to complete a study of this kind is a vibration meter, such as the Larson Davis: HVM200. This device averages around $3,000 and can accomplish the measurements that this study requires. Additionally, the author did not have a triaxial seat pad (SEN027) to use in this study. It was verified from a member of the bioenvironmental engineering section at MAFB that there is not a vibration meter to utilize. No local agencies were willing to oversee or loan out professional equipment for use in this study. A possible limitation in performing this study or future studies similar to this one is receiving special access and permission to travel with and collect data on members of armored vehicles. Agencies that operate armored vehicles are inherently confidential by design. The weather was also a limitation that had to be taken into consideration because in December 2016, there was greater than 40 inches annual snowfall, a record in Minot ND. Due to the massive amount of snow, the amount of opportunity for movement on gravel roads was minimized.

Delimitations:

The limitations to this study were delimited in the following ways:

- The gold standard vibration measurement tool was substituted with the consumer electronic; 5th Generation iPod Touch

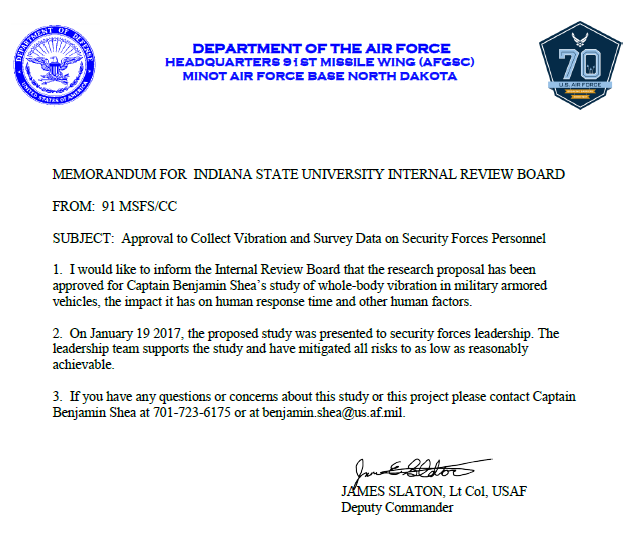

- This study was coordinated with security forces (SF) leadership, Wing Safety, and the Unit Codes shop at MAFB. Together, all of these agencies were responsible for ensuring security and procedures occurred while data was collected. All electronic devices remained outside of restricted areas and mission requirements always had precedence over testing protocol. The risk of security compromise or impact to military operations was declared to be very low. Therefore, on January 19, 2017, SF leadership and MAFB agencies approved the methods presented in this study (Appendix D).

Assumptions of the Study

It was assumed that the survey data collected from the SF members were accurate, precise, and truthful. In the research survey, the participants were assumed to have a history of back injuries that were caused by a multitude of factors. It was beyond the scope of this study to make conclusions on what factor was most causing the back injuries. It was assumed that survey data from vehicle operators were truthful in regard to their perception of back pain and other stimulus encountered while performing driving duties. The population set at MAFB was one set out of three total military bases that perform the same line of work. This became a challenge for the statistical reliability of the study. The population of armored vehicle operators is specialized in these areas. Thus, there was a gap in comparative data from similar studies that considered mine workers and heavy construction laborers, which, have a much greater population size.

Definitions

Whole-body Vibration: Results when the entire body is supported – through standing, sitting or reclining – on a piece of equipment and absorbs the mechanical vibration from that equipment (Morrison, 2009).

Armored Vehicle: The HMMWV is a highly mobile, diesel-powered, four-wheel-drive tactical vehicle that uses a common chassis to carry a wide variety of military hardware ranging from machine guns to tube-launched, optically tracked, wire command-guided (TOW) anti-tank missile launchers (General, 2016).

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Lower-back Pain and Discomfort

Lower back pain is one of the major concerns that can result from whole-body vibration. When workers experience an uncomfortable work environment, it is often ergonomics causing the back pain. In the U.S. in 2014, there were 79,140 cases that involved days away from work due to back (including spine, spinal cord, and unspecified) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). It is conveyed that lower back pain can be prevented through improved posture, training, and improved seating systems. For instance, Bose, the same company that produces state of the art acoustics has also designed a highly impressive vibration reduction system that improves the quality of life for professional truckers. This same technology could be used to improve the lives of military and armed forces who are driving in austere conditions that cause high levels of vibration. Although there appears to be a relationship between lower-back pain, discomfort, and WBV; the science behind it is not completely understood. Often the difficulty is that workers exposed to WBV also work in environments that contain many physical risk factors such as “awkward postures, prolonged sitting, as well as loading and unloading materials from a vehicle” (Santos, 2008).

In another study Mansfield (2014) found that participants sat for a long period and experienced back pain regardless of vibration exposure. The results revealed that as the amount of time sitting increased, so did the level of back pain. This study questioned participants on their level of discomfort at five-minute intervals while driving. They noticed that when subjects were exposed to whole-body vibration and were sitting, even more discomfort was reported. This study found that posture changes are important to ensuring comfort. If a subject cannot adjust themselves, then they will experience discomfort more quickly than someone who is mobile. It was observed that an additional amount of vibration can be transmitted into the body via the arms. Likewise, it is also possible for the arms to act as a vibration absorber. Mansfield also conducted experimentation on a control group that sat in the same vehicle while parked in a lab. They found that discomfort levels were only slightly greater for the driving group than the parked group. After 17.49 minutes, the study found that there was a significant effect on comfort level. In a passenger train WBV study by Nassiri (2011), there was found to be very little statistically significant relationships between descriptive data and health symptoms. This lack of correlational data supports the conclusion that WBV is probably not the main factor for passenger discomfort on trains.

Consumer Electronics as Measurement Tool

In this study, Wolfgang was able to measure whole-body vibration amplitudes to within 95% confidence of ±0.06 m s−2 root mean square (r.m.s) for the vertical direction for mining equipment. This author was able to provide this strong support through comparing the data collected simultaneously from an iPod Touch and gold standard equipment; SV106 and a Type 4447 Human Vibration Analyzer. There was forty-two trials ranging from 10 to 55-minute recordings. The r.m.s values were used in calculating and arriving at the high confidence interval for the vertical direction. The author concluded that the iPod Touch underestimated true vibrations by 0.073 m/s2, which is likely to be satisfactory for use as a safety-screening tool for WBV exposure (Wolfgang R. , 2014).

Often mining equipment operators are subject to twelve-hour shifts. The variables and human factors that studies from the University of Queensland considered were: roadway conditions, suspension design and maintenance, seat design, condition and adjustment, tire design and maintenance, and driver behavior (e.g., speed) (Burgess-Limerick R. L., 2015). It was found that ISO 2631.1’s requirement for measurement and evaluation is complicated and expensive; therefore, monitoring this human health hazard occurs very infrequently. In order for control measures to be implemented, sources of hazard must be identified.

Whole-body Vibration

Heavy machinery and large equipment are often the source of whole-body vibration. WBV has been known to cause many illnesses including: motion sickness, spinal injury, and muscle fatigue (Goetsch, 2011, p. 513). Short-term exposure is linked mostly to benign physiological effects such as loss of balance and blurred vision. Many researchers believe that a person’s motivation, information collection, and processing can be effected by WBV (Smith, 2005). An expert in the field of Occupational vibration, Donald Wasserman estimates that “Up to 8 million workers are exposed to some type of vibration. Of these, it has been estimated that more than half will show some signs of injury” (Wasserman D. , 1986). The most commonly reported adverse effect of WBV is musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). Additionally, “The total cost of low back pain to the United States economy is $90 billion a year”. (Pope, Magnusson, & Wilder, 1998)

In the study of whole-body vibration, the cumulative exposure was determined by intensity and duration. Vibration is a type of motion that is measured as a quantity of acceleration. The vector forces are in the directions of up-down, side-to-side, and front-to-rear. (Wasserman D. , n.d.) “Knowing how the length of exposure to whole-body vibration is associated with the risk of developing an injury is one of the big questions researchers are trying to tackle” (Morrison, 2009). A key concept that has been noted in previous studies of whole-body vibration is that all objects have a speed at which they naturally vibrate (Smith, 2005). This is an important factor to consider when research focuses on varying sizes of vehicles, conditions, and the speed at which they normally travel.

Long Term Effect

In Pope et al’s (1998) study on WBV and lower back pain they discovered career vibration exposure was related to low back, neck, and shoulder pain. A study by Dupuis and Christ found that tractor operators driving more than 700 hours per year had 61% pathologic changes of the spine. As the number of career-hours increased to greater than 1200 hours, the percentage of operators with changes to their spine also increased to an astounding 94%. Studies focusing on coal mining (E, 1972), truck drivers (U, 1969), and bus drivers (AL, 1983) have each found long-term correlations with WBV and damage to the spine.

Lab Studies and Biomechanics

Santos et al investigated biomechanical responses before and after 60 minutes of sitting, with and without vertical WBV. Lab based scenarios have taught researchers that exposure to vibration “May cause spine pathology through mechanical damage, most notably to the vertebrae, vertebral endplates, intervertebral discs and low back musculature” (Wikstrom, 1994). This study was interested in determining whether the increase of muscular activity observed during vibration could lead to muscular fatigue. The authors found that muscle activity was small after sitting for 60-minutes. After measuring and comparing muscle fatigue, they discovered very little difference between patients who sat with WBV and those who sat without WBV. This study provides a good example of a study of WBV that fails to reject the null hypothesis.

In a study by Shaman (2005) they found that after truck drivers had been exposed to 2.5 hours of “real-time” truck environment there was a significant change in postural stability and balance. This study, like others of its kind, supported a time dependent increase in loss of balance. The overall effect of WBV is not completely clear, but it has been reported that the somatosensory and visual systems are affected by vibration (Martin, 1980); (Peli, 2003); (Roll, 1980). If this is true, then WBV will be a factor in the overall response-time of drivers and will create an increased risk of vehicle rollover due to late response and often overcorrection.

In a biological study by Ariizumi, (1985) they investigated the concentrations of noradrenaline (NA), dopamine (DA), and serotonin (5-DT) in the brains of Wistar rats. The biochemical effect of vibration in the body is known to effect the central nervous system. Immediately after being exposed to whole-body vibration, biochemical assays were taken of the brain in order to measure the concentrations of the three chemicals. The study found that as vibration increased there was a significant increase of dopamine in the cortex of the brain. This study provided raw evidence that vibration induces a biochemical response.

Muscle Fatigue

The breakdown of muscle in humans is a symptom of whole-body vibration. In fact, Hansson (1991) demonstrated that vibration increases both the speed and magnitude of the development of lumbar muscle fatigue. A fatigued body will increase the chance and severity of an accident. Fatigue can be defined at the cognitive, affective, or physical state of tiredness or weariness caused by exertion (Troxel, 2015). In Hosten’s (2005) study they focused on the key factor that vibration causes back pain because it causes the requirement for spinal muscle support. Using electromyography (SEMG) the authors of this study were able to model and measure specific muscle response and fatigue along a timeline. In a similar study, the authors found compelling evidence that muscle fatigue and muscle oxygenation oscillation were frequency dependent with WBV at 4.5 Hz (Li Z. , 2012). This depletion of oxygen explains at a physiological level what is happening to muscles when vibration and fatigue is occurring.

Field Studies in Military, Tractors, and Trains

In the Naval field study of the MH-60S Helicopter, there was a baseline study of the effects of whole-body vibration and pilots. This study found that chairs in this aircraft were designed for crash survivability and not necessarily for comfort or ergonomics. The same is true in armored vehicles that are in use today. The author of this study suggests that a different kind of protection is necessary as we transition to new technologies and replacement vehicles. Harrer found that mission readiness decreases as flight time increases (2006). The goal of this research was to compare two different seat cushions; the standard cushion and the improved anti-vibration cushion. The results of this study found that the vibration exposure was less in the anti-vibration seats, but the threshold limit value (TLV) was still too high and exposed the pilots to an unacceptable “risk of injury, lack of mission readiness, and possible equipment damage”.

In another military study by Wells (1987), they focused on the impact that vibration has on pilot reading performance and the onset of back pain during flights. The study found that the type of seated position and task has an overall impact on when back discomfort begins. The study recommended that changes in seat design, such as improvement in back and thigh support would improve pilot performance.

In a study of AH-1S Cobra helicopters, the author’s smartly instructed the pilots to report any low back pain or discomfort because of their known tendency to play down physical complaints (Froom, 1987). This author provided a quality discussion of the fact that questionnaires are often subjective. Because of this phenomenon it can be realized that any differences seen in questionnaire results can be caused by variation due to imprecise methodology, which can occur randomly in any study.

Truck Rollovers

The Transportation Research Board provides the conclusion that the following actions most commonly lead to rollover accidents: driving too fast for conditions, illegal maneuvering, inadequate evasive action, and poor directional control (Pape, 2012). They have also determined that the following human factors contributed most to the unsafe acts listed above: info gathering, driver state, physiological condition, obesity and health, alcohol and drug involvement, and vehicle control. It is reasonable to accept that “the main sources of harmful WBV in vehicles are rough roads and surface conditions”, which are a factor in rollover accidents (Arslan, 2015). Because behavior is found to be a large portion of what drives human factors, the authors found that monitoring behavior was a good method to prevent rollovers.

Analysis and Statistics

The two primary methods of data analysis focus on amplitude composition and frequency composition of a time-history. Each category of data garners insight into the severity and type of vibration occurring. The amplitude used in vibration research is known as the root mean squared (r.m.s) amplitude and is defined as the square root of the mean of the time-history (n) over the square of the vertical distance of the graph from the rest state.

R = root mean squared

x = vertical distance from rest state to the wave crest

Using the standard deviation and mean of amplitude and frequency derived from within a time-history, researchers can estimate the vibration dose value (eVDV). This is useful because the dose value can be compared to doses of asymmetric times and OSHA TLVs.

R = Root Mean squared amplitude

Ts = Time in seconds

WBV Control Measures

The Transportation Research board believes that safety training, company culture, constant reinforcement of awareness, vigilance against distractions and fatigue, health and wellness, and involvement of driver families are the key factors in preparing and maintaining drivers that work with WBV. Vibration attenuating seat and correct ergonomic layout of working environments could reduce the factors that are listed above (Pope M. , 1998).

Human Response Time

Many studies have found that response time is a valuable measure of human performance (Jastrow, 1890) (Luce, 1991). It is also true that most computers and consumer devices collect timestamps that are delayed and inaccurate. Through computer programming breakthrough’s the RTbox, has been engineered and invented, to collect highly accurate response time measurements. The device uses a very accurate time source and can overcome delays in electrical signal, debouncing of keys, and heightened event detection (Li X. , 2010).

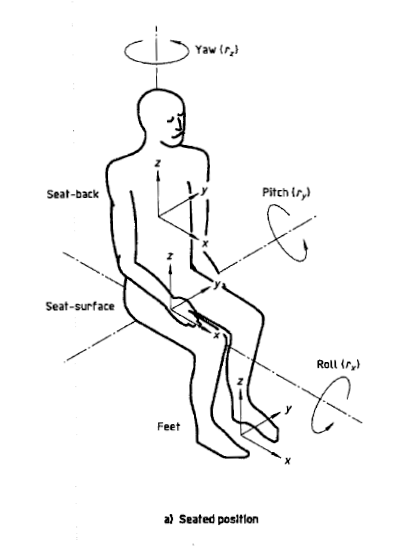

ISO 2631.1

The International Standard for the evaluation of human exposure to whole-body vibration is found within the ISO 2631.1. The standards overall purpose is to provide standardized methods for quantifying WBV and its relation to human health and comfort, the probability of vibration perception, and the incidence of motion sickness. The frequencies that will be considered using the ISO will be 0.5 Hz to 80 Hz for health, comfort and perception, and 0.1 Hz to 0.5 Hz for motion sickness. For frequencies around 4.5 Hz, lower-back pain becomes prevalent (Pope, Magnusson, & Wilder, 1998). Figure one illustrates the X, Y, and Z axis that was studied in accordance with the ISO. All measurements were collected as defined by the ISO. If the crest factor is below or equal to nine, then the r.m.s acceleration values are “normally sufficient” measures of severity for the evaluation of human vibration effects. The crest value is defined as the modulus of the ratio of the maximum instantaneous peak value of the frequency-weighted acceleration signal to its r.m.s value. The crest factor does not necessarily indicate the severity of vibration. (International Standard, 2004). In Burgess-Limerick’s (2012) study, they questioned the validity of the crest factor as an additional measure. The reasoning behind this is that the value is sensitive to the duration of measurement, in that the longer the measurement duration, the greater probability of a higher peak value. Researchers will need to use good judgement in determining if the crest value, as outlined by the ISO, is a good fit for each study.

Figure 2. ISO illustration of the vibrational vectors seen in the X, Y, and Z axis.

METHODOLOGY

Data collection is crucial in this study and was recorded in the form of a questionnaire, response-time test, and vibration data. The author was present to proctor all of the testing. The author was dressed in casual non-military clothing in order to facilitate data collection and avoid any bias that could be caused by rank or superiority. The questionnaire was the first set of data collected and was given to participants using pen, paper, and clipboard (Appendix A). A post questionnaire occurred at the end of testing. The participants were selected using convenience sampling and the study data was collected nearby the following North Dakota cities: Ryder, Makoti, Berthold, Mohall, and Maxbass. Additionally, control groups were subject to paved road conditions. All road types driven in this test were roads that were safe and commonly traveled.

The questionnaire was designed similarly to Maeda (2003) et al’s study that provided great insight into the relationship between vibrations and comfort while in a seated wheel-chair environment. Demographic information and history of experience with respect to workplace vibration was collected. The questionnaire takes place prior to operating and driving in an armored vehicle.

After the questionnaire was administered and immediately prior to beginning travel a reaction test was conducted.

Figure 3. An armored vehicle operator conducts the reaction test on an iPad

This test was completed using the 7.9” iPad Mini 2. The iOS Application, “Reaction Test Pro” by Freedom Apps calculated the average response time. The participant taps the “start” button on the touch screen, next the indicator turns orange, and they wait for the indicator to change to red. When the indicator light changes from orange to green, the participant presses the “stop” button. The program calculated an average response time based upon three attempts. After completing the reaction test, the participant entered the driving portion of the study.

The vibration statistics were collected in the X, Y, and Z direction while driving and a timeline of acceleration data was generated. In addition to a driver and at least one team member, the author sat in the back seat and recorded observations for later analysis. The data was measured using a 5th generation iPod Touch. This device was secured to the driver’s seat using adhesive tape with the touch screen facing up, see figure 4. Measurements were made beneath the ischial tuberosity. The device ran the iOS application “WBV” by Byte Works, Inc. that measured whole-body vibration and utilized the onboard accelerometer according to ISO 2631-1 and previous research accomplished by Wolfgang et al.

Figure 4. The iPod Touch is taped to the operator’s seat

The minimum duration of measurement required by the ISO is 108s, however, the goal set out for this study was to assemble measurements in operation of HMMWV’s of approximately 15 minutes on average. From the time vibrations were recorded, all significant events were concurrently logged in a notebook using a stopwatch. Data that was collected, was inconsistent with normal travel, and found to be an outlier were logged and later removed from the data set. The author filtered and purged data collected immediately prior to starting and stopping data collection.

The root mean square (r.m.s) was the cumulative score that was calculated and used in accordance with ISO 2631.1. Upon arrival at the driver’s destination, the reaction test was completed again and answered the post drive questions of the questionnaire. The vibration data, differences in reaction time, and report of lower-back pain were used to make statistical inferences about the impact that whole-body vibration had on armored vehicle operators.

Population and Sample Selection

The population that was studied consisted of military armored vehicle operators (AVO). There was a random sampling of 22 AVOs. Of these 22 operators there was 22 vibration trials conducted. All but one AVO was a male. AVOs had a median age 23, height 5’10, and weight 185 lbs. On average, AVOs carried 40 additional pounds of weight or body armor. AVOs had performed this job duty an average of 2.5 years prior to this study. The AVOs reported driving a mean of 3.8 times per week and 5.9 hours per day. None of the AVOs had taken a questionnaire of this kind before.

Protection of Human Subjects

The population tested was briefed to operate in safe and otherwise normal conditions. The testing did not negatively affect the mission of the 91st MW SF. They did not deviate from any safety protocols while collecting data. Personally identifiable information or sensitive information was not collected during the study. The Indiana State IRB approved this study in the expedited review type on April 20, 2017. See Appendix E.

Instrumentation

A 5th generation iPod Touch (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA) (123 x 59 x 6 mm, 88g) was utilized to record the vibration data. The device had a factory calibrated LIS331DLH accelerometer (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) that provided three dimensional 16 bit data output configured to a range of +/- 2g. The maximum sampling rate was restricted by the operating system to a nominal 100 Hz (inter-sample interval of 0.01s). A second generation iPad Mini was used to retrieve response data.

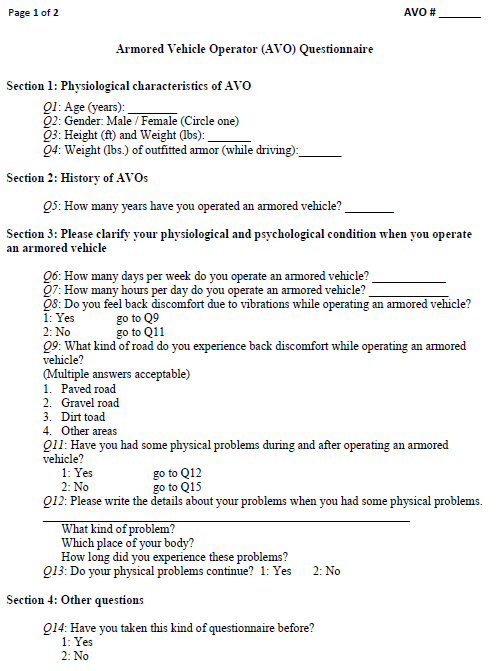

Questionnaire Administration

A questionnaire was used to determine descriptive data such as age, gender, perceived back pain, and weight of equipment on his or her body. It used the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale Rating to help participants communicate as accurately as possible their experience of back pain. A post-test questionnaire allowed the participant to express back pain experienced during and immediately after the drive. This questionnaire used objective questions in order to reduce error or bias. See Appendix A.

Data Collection

Data was collected using: a pen, clipboard, battery backup, and paper for all questionnaires. Data was recorded within the internal storage of the iPod. Data was exported via email to a Microsoft computer for further analysis in IBM SPSS Statistics 22. A database was designed using Microsoft Access in order to facilitate organized reporting seen in Appendix B.

RESULTS

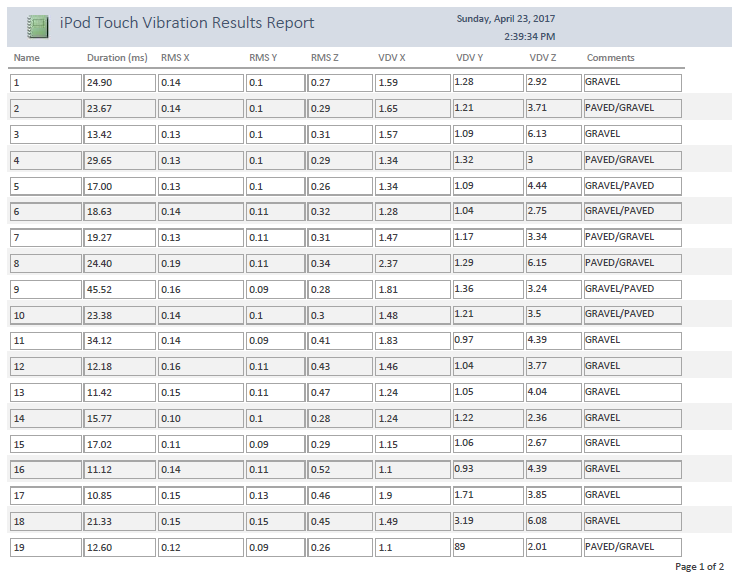

Vibration Findings

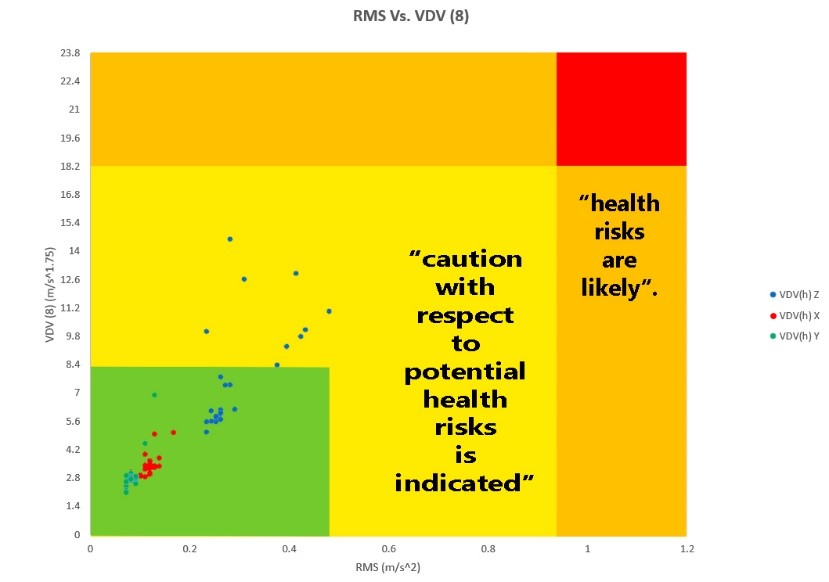

In this study, we collected 22-minute average duration whole-body vibration measurements from 22 Humvees during normal operation in the Minot AFB North Dakota missile complex. Figure 5 illustrates where each trial fell on the risk spectrum for WBV.

Figure 5. The image shows all 22 vibration recordings with the background coloration indicating risk levels.

The vertical accelerations measured as r.m.s ranged from 0.26 m/s2 to 0.52 m/s2 r.m.s. The VDV(8) measurements ranged from 5.03 m/s1.75 to 15.09 m/s1.75. Two of the 22 r.m.s measurements were within the ISO 2631.1 Health Guidance Caution Zone, which is between 0.47 and 0.93 m/s2. Nine of the eighteen VDV(8) measurements were within the Health Guidance Caution Zone. The corresponding values for the VDV measure expressed as an eight-hour equivalent are between 8.5 m/s1.75 and 17 m/s1.75. The measurements of this study are considered short duration measurements, being 10 to 45 minutes and averaging about 22 minutes total. There were approximately eight hours total vibration data recorded in this study. This study discovered that the only vibration acceleration axis of any concern was the z-axis for AVOs. For exposures within the Health Guidance Caution Zone, “Caution with respect to potential health risks is indicated” (International Standard, 1992).

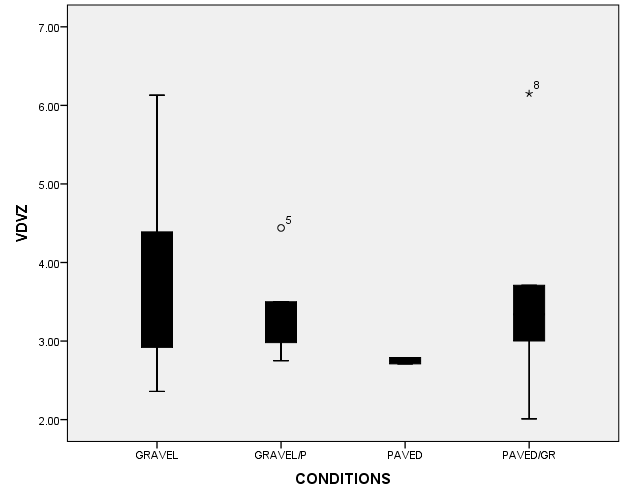

In figure 6, notable difference appeared in WBV dose, dependent on the type of road conditions present. The vibration dose vector in the z-axis (VDVZ) is much higher and unpredictable in those trials taking place on gravel than those conducted on pavement. The pavement trials are very well controlled and include exposures at or around 3.0 m/s2 VDV.

Figure 6. The stem and leaf plot shows the Z-axis exposure as related to the road conditions.

Questionnaire Findings

This study found that half of the AVOs attributed back discomfort due to vibrations while operating an armored vehicle. Of those admitting to back discomfort, 14% identified paved roads, while all identified gravel roads as the location they experienced back discomfort most. 45.5% of AVOs reported having had some physical problems during and after operating an armored vehicle. The most common reported physical problems were focused on the back, knee, and legs. In this questionnaire, 40% of those experiencing problems noted that the physical problem subsided a short time after exposure. The satisfaction found in operating armored vehicles in the Minot environment was found to be mostly neutral with 41% of AVOs responding neutral. 32% of AVOs responded favorably to being satisfied with operating the Humvee. 27% of AVOs were unsatisfied. On average, AVOs reported mild pain both before and after exposure to WBV and operating the armored vehicles. A slight increase for pain was reported by the AVOs. Statistically, there was no difference in the duration of driver trials and the perception of pain afterwards. No significant relationship occurred between the weight of body armor and the perception of pain afterward.

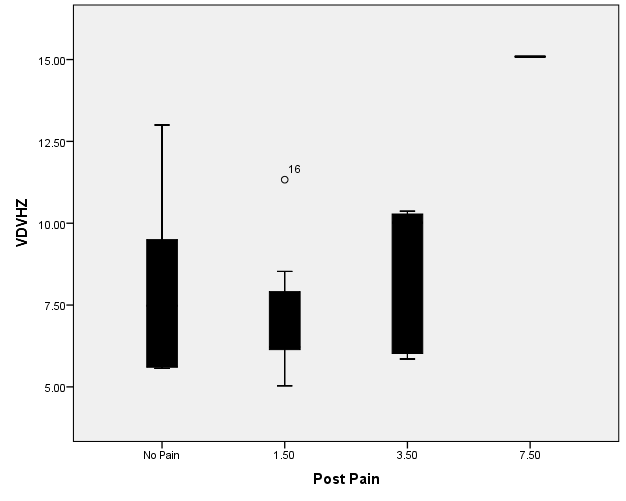

Figure 7. The stem and leaf plot shows the Z-axis exposure as related to Post-Questionnaire perception of pain (see Appendix A).

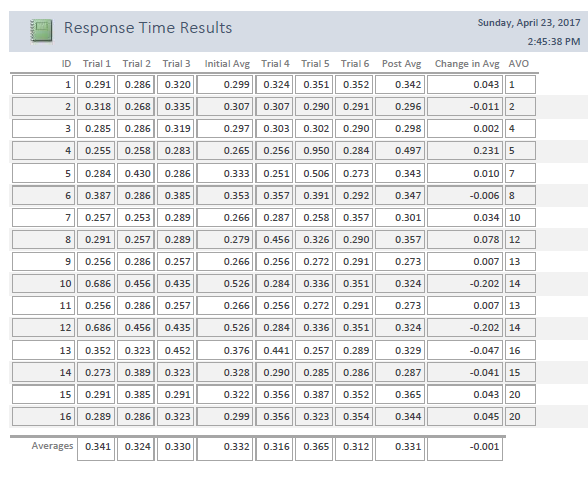

Response-time Findings

Response times found in this study were extremely consistent throughout the trials. The mean response time for AVOs was .3318 seconds before exposure and .3312 seconds after exposure. In these trials, no difference occurred in reported response time after driving the vehicle. The mean change in response time was .0006 with a standard deviation of .10080.

DISCUSSION, CONCLUSIONS AND RECCOMENDATIONS

Hypothesis and Outcomes

The relationship between the dose of WBV and the perceived amount of lower-back pain, the mean values for no-pain, mild-pain, and moderate-pain are 8.6 m/s1.75, 7.02 m/s1.75, and 10.2 m/s1.75 respectively. Dose-response relationship cannot be strongly supported with the data collected. No relationship or correlation was supported because there was not a wide spectrum of pain perception found in this data. The author therefore fails to reject the null-hypothesis, which, states that there is statistically no significant relationship between reported lower-back pain and whole-body vibration dose in an armored vehicle.

In testing response-times, we found no statistical difference between the pre-test and post-test results. Response-times were unaffected by the activity of driving the armored vehicles. The author also fails to reject the second null-hypothesis, which, states that there is no significant correlation between the dose of whole-body vibration and response-time in an armored vehicle.

In order for this style of research to have scientific value, more accurate and precise equipment is required. In measuring response-time, the application would need to be very precise because human response time is not easily measured. Fast action cameras or lasers would likely be required to receive a proper measurement of response time in vehicle operators. Through this study, it is apparent that additional research is necessary on the side of human health and effects of WBV in a long-term study basis. Back injuries and degradation of health do not appear to happen overnight. This study has illustrated the reality that there is a need for some sort of improvements in the management of ergonomic risk for AVOs. There exists the potential for increased risk to the health of these operators, as indicated by the WBV dose readings. Studies are necessary in order to implement new ergonomic technologies for AVOs. Great need exists for an engineered device that can manage the extra weight that AVOs are subject to on a daily basis while driving. In the future, it may be beneficial to create a study focused on researching the possibility of inventing a device that reduces the strain of muscles and fatigue. This strain occurs while sitting for long periods. The study would be useful in order to support the implementation of a force-wide Body Armor Weight Arrest System (BAWAS). This device would determine a safe way to manage the extra weight while driving in addition to providing the defense required for a wearer of body armor.

Recommendations for Further Research

In order to improve research design, a very specific and controlled environment with a driver’s course designed for testing response times on gravel roads and paved roads would need to exist. This research study was designed as a relatively small random sampling of very dynamic and different road conditions throughout rural North Dakota, which, created a great amount of random error. The sampling size was not large enough to compensate for this error. This study collected short durations of exposure to WBV. If a larger sample size and a longer duration of exposure could be collected then the author might have found different results.

The response-time test and questionnaire could be used at the beginning and end of a work-shift in order to further capture the full range of work required of a missile security forces member. This study only provides a snapshot into the actual workplace stress that occurs over a working week. The response-time methods used in this study are inherently inaccurate and roughly estimated.

This study has successfully built a quantitative data set to begin building an understanding of WBV and the human health effects of AVOs. The potential for improving quality of life for these operators and improving the risk management in this job is immense. Any improvements in ergonomics and engineering solutions will lead to a better working environment for AVOs. Further research is necessary to improve our understanding of the risks involved with WBV.

Air Force Global Strike Command Director of Safety. (2016, July 19). The Big 6: Avoiding the Human Factors Wheel of Misfortune.

AL, B. (1983). Health survey of professional drivers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 9:36-41.

al, Z. L. (2012). Wavelet analysis of lumbar muscle oxygenation signals during whole-body vibration: implications for the developement of localized muscle fatigue. Europian Applied Physiology, 3109-3117.

Ariizumi, M. e. (1985). Effects of whole body vibration on biogenic amines in rat brain. Brittish Journal of Industrial Medicine, 133-136.

Arslan, Y. (2015). Experimental Assessment of Lumped-parameter Human Body Models Exposed to Whole Body Vibration. Mechanics in Medicine and Biology, 1-13.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015, November 19). Economic News Rease. Retrieved from United States Department of Labor: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh2_11192015.htm

Burgess-Limerick, R. (2012). How on earth moving equipment can ISO 2631.1 be used to evaluate whole body vibration. Health & Safety Research & Practice, 4(2), 14-21.

Burgess-Limerick, R. L. (2015). An iOS application for evaluating whole-body vibration within a workplace risk management process. Journal of Occupational and Envrionmental Hygiene, 12(7), 137-142.

Cann, A. e. (2003). An exporatory study of whole-body vibration exposure and dose while operating heavy equipment in the construction industry. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 999-1005.

E, C. (1972). Iron and steel industry as well as mining. Kommiss Europ Gem Generaldir Soz, 72.

El Falou, W. e. (2003). Evaluation of driver discomfort during long-duration car driving . Applied Ergonomics, 249-255.

Froom, P. (1987). Low Back Pain in the AH-1 Cobra Helicopter. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 315-318.

General, A. (2016). HMMWV. Retrieved from Features & Design: http://www.amgeneral.com/vehicles/hmmwv/features.php

Goetsch, D. L. (2011). Occupational Safety and Health for Technologists, Engineers, and Managers. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Griffin, M. (1996). Methods for Measuring and Evaluating Whole-body Vibration Exposures. In Handbook of Human Vibration (pp. 453-483). New York: Acedemic Press.

Hansson T, M. M. (1991, August). Back muscle fatigue and seated whole-body vibrations: an experimental study in man. Clinical Biomechanics, 6(3), 173-178.

Harrer, K. e. (2006). A Field Study: Measurement And Evaluation Of Whole Body Vibration For MH-60S Pilots . Retrieved from Introduction; Proceedings Of The First American Conference On Human Vibration: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/8453

Hostens, I. e. (2005). Assessment of muscle fatigue in low level monotonous task performance during car driving. Electromyography and Kinesiology, 266-274.

International Standard. (1992). Mechanical vibration - Laboratory method for evaluating vehicle seat vibration - Part 1: Basic requirements (Vols. 10326-1).

International Standard. (2004). Mechanical vibration and shock - Evaluation of human exposure to whole-body vibration (Vols. 2631-1). 1997.

Jastrow, J. (1890). The time relations of mental phenomena. New York: Hodges.

Li, X. (2010). RTbox: A device for highly accurate response time measurements. Behavior Research Methods, 212-225.

Li, Z. (2012). Wavelet analysis of lumbar muscle oxygenation during whole-body vibration: implications for the development of localized muscle fatigue. Europian Journal of Applied Physiology, 3109-3117.

Luce, R. D. (1991). Response times: Their role in inferring elementary. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lynas, D. e. (2015). Whole-Body Vibration Exposures in Underground Coal Mining Operations. Retrieved from http://www.ergonomics.uq.edu.au/wbv/WBVpod/Resources_files/HFES%202016%20preprint.pdf

Maeda, S. (2003, July). Relationship between Questionnaire Survey Results of Vibration Complaints of Wheelchair Users and Vibration Transmissibility of Manual Wheelchair. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 82-89.

Mansfield, N. e. (2014). Combined Effects of Long-Term Sitting and Whole-Body Vibration on Discomfort Onset for Vehicle Occupants. Automotive Engineering, 1-8.

Martin. (1980). Effects of whole-body vibrations on standing posture in man. Aviation, Space, and Enironmental Medicine, 778-787.

Morrison, K. W. (2009, October 1). Whole-Body Vibration. Retrieved from Safety and Health Magazine: http://www.safetyandhealthmagazine.com/articles/whole-body-vibration-2

Nassiri, P. e. (2011). Train Passengers Comfort with regard to Whole-Body Vibration. Low Frequency Noise, Vibration and Active Control, 125-136.

Ng, J. e. (2003). Effect of fatigue on torque output and electromyographic measures of trunk muscles and during isometric axial rotation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 374-381.

Paddan, G. &. (2002). Effect of seating on exposures to whole-body vibration in vehicles. Sound and Vibration, 215-241.

Pape, D. e. (2012). Role of Human Factors in Preventing Cargo Tank Truck Rollovers. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

Peli. (2003). Motion perception during involuntary eye vibration. Experimental Brain Research, 431-438.

Pope, M. (1998). Low back pain and whole body vibration. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 241-248.

Pope, M. H., Magnusson, M., & Wilder, D. G. (1998). Low Back Pain and Whole Body Vibration. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 241-248.

Roll. (1980). Effects of whole-body vibration on spinal reflexes in man. Aviation, Space, and Enironmental Medicine, 1227-1233.

Santos, B. e. (2008). A laboratory study to quantify the biomechanical responses to whole-body vibration: The influence on balance, reflex response, muscular activity and fatigue. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 626-639.

Seidel, H. e. (1980). On human response to prolonged repeated whole-body vibration. Ergonomics, 191-211.

Shaman, A. e. (2005). Postural Stability of Commercial Truck Drivers: Impact of Extended Durations of Whole-Body Vibration. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 49, pp. 1810-1814.

Smith, D. L. (2005). Whole-Body Vibration: Health effects, measurement and minimization. Professional Safety, 35-40.

Troxel, W. e. (2015). Evaluating the Impact of Whole-Body Vibration on Fatigue and the Implications for Driver Safety. Retrieved from Research Reports: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1057.html

U, S. (1969). Comparative studies on heavy duty truck drivers and office workers on the question of occupational injury to the vertebral column and the joints of the upper extremities.

Wasserman, D. (1986). Human Aspects of Occupational Vibration (Advances in Human Factors/Ergonomics). Elsevier Science.

Wasserman, D. (n.d.). Galson Labs. Retrieved from OCCUPATIONAL VIBRATION: WHO IS AT RISK?: http://www.galsonlabs.com/resourcecenter/bulletin.php?c=25

Wells, M. (1987). Flight Trial of a Helmet-Mounted Display Image Stabilization System. Aerospace Medical Association, 319-318.

Wikstrom, B. K. (1994). Health effects of long-term occupational exposure to whole-body vibration: a review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 273-292.

Wisconsin, U. o. (2017, January 23). RMS Amplitude. Retrieved from https://csd.wisc.edu/vcd202/rms.html

Wolfgang, R. (2014). Using Consumer Electronic Devices to Estimate Whole-Body Vibration Exposure. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, D77-D81.

Wolfgang, R. e. (2014). Can an iPod Touch Be Used to Assess Whole-Body Vibration Associated with Mining Equipment? The Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 1-5.

ARMORED VEHICLE OPERATOR QUESTIONNAIRE

VIBRATION DATA REPORT

RESPONSE-TIME DATA REPORT

COMMITMENT LETTER

EXPEDITED REVIEW

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE IN RESEARCH

<script>

/**

- RECOMMENDED CONFIGURATION VARIABLES: EDIT AND UNCOMMENT THE SECTION BELOW TO INSERT DYNAMIC VALUES FROM YOUR PLATFORM OR CMS.

- LEARN WHY DEFINING THESE VARIABLES IS IMPORTANT: https://disqus.com/admin/universalcode/#configuration-variables*/ /* var disqus_config = function () { this.page.url = https://shea08.github.io/ISU_Project; // Replace PAGE_URL with your page's canonical URL variable this.page.identifier = /ISU_Project/; // Replace PAGE_IDENTIFIER with your page's unique identifier variable }; */ (function() { // DON'T EDIT BELOW THIS LINE var d = document, s = d.createElement('script'); s.src = 'https://shea08.disqus.com/embed.js'; s.setAttribute('data-timestamp', +new Date()); (d.head || d.body).appendChild(s); })();

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)