by Francis Tseng

+

+The application that introduced peer-to-peer (P2P) computing to the mainstream was file sharing, services like Napster, Kazaa, Gnutella, and BitTorrent. For me, these programs were the first time the contradiction of artificial scarcity—the imposed scarcity of infinitely replicable digital information—and the excessive measures that were used to enforce it became startlingly clear. Over time, I encountered the term P2P in other settings and alongside other ideas—democratic governance, communalism, autonomy, cooperatives—and I started to see the purchase this idea had beyond file sharing and networking protocols.

+

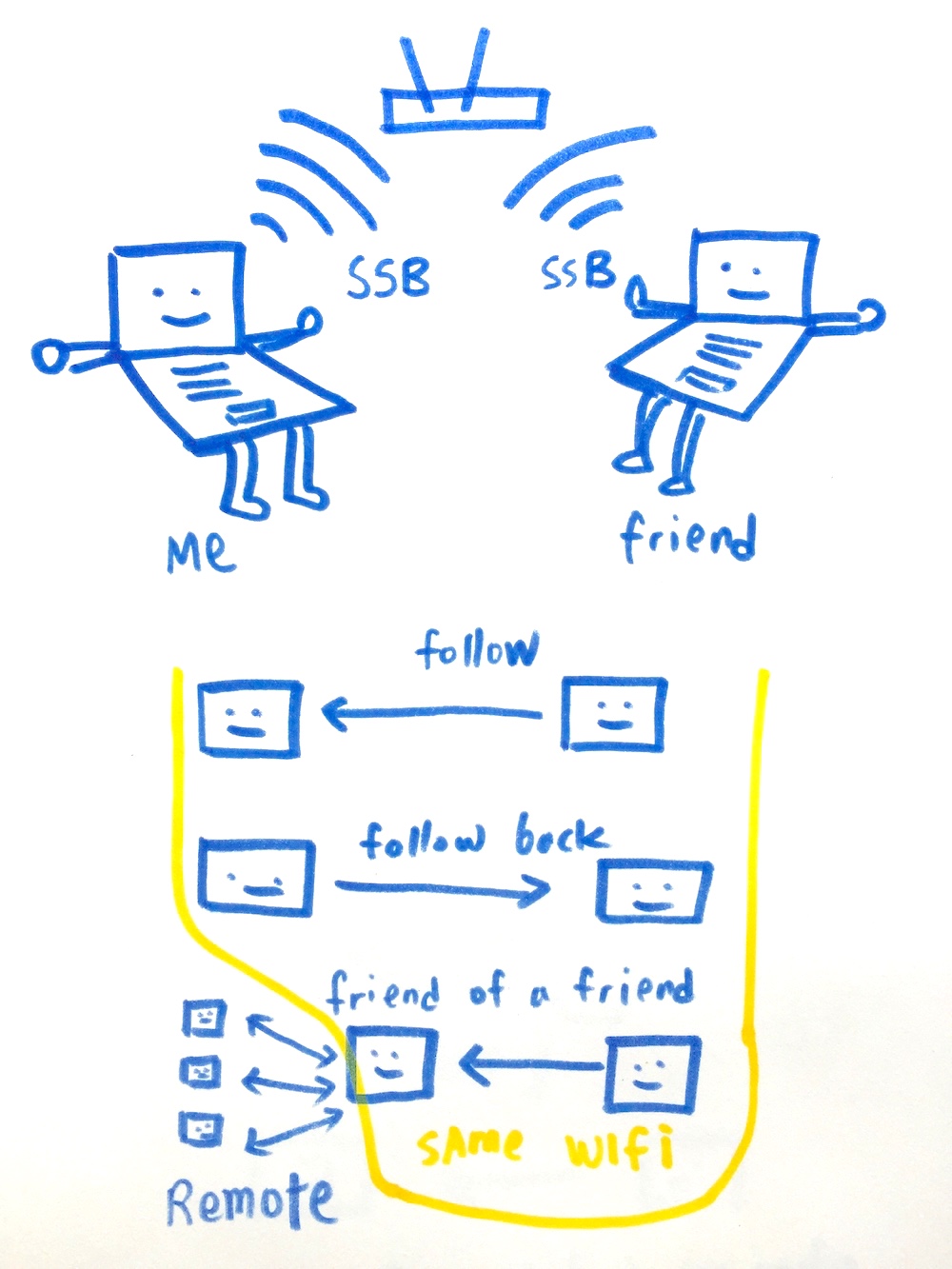

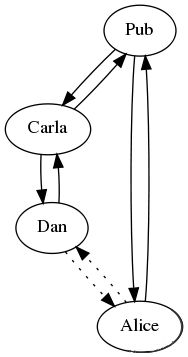

+The P2P Foundation’s mission and strategic priorities, for example, extend the early P2P ideas of open culture and exchange into values of cooperative living and regenerative production. Scuttlebutt, a more recent P2P social networking protocol, has its own “principles stack” that similarly advocates pluralistic exchange and mutual interdependence. It’s beautiful how, at least in the ideal scenario, by using a P2P service we are helping others access it as well. P2P is both an acknowledgment of our shared needs and an example of how cooperation helps us fulfill those needs.

+

+Over the years, I’ve followed along with P2P projects because of these shared values, and I always find it exciting when new projects emerge. It seems that P2P is experiencing something of a renaissance, likely due to the frenzy around blockchain (which purports to offer something similar to P2P) and the increasing popular anxiety around centralized internet services like Facebook.

+

+Urbit, “a personal server built from scratch,” first came across my radar a couple of years ago. Urbit positions itself as a P2P project, but it stands out in contrast to other P2P projects, mainly because the person behind it, Curtis Yarvin, seems antithetical to what I understand P2P to represent.

+

+My central question is this: Is Urbit a project that should be supported?

+

+We can further break this down into two parts. First, Urbit’s marketing materials correctly identify that concentrated data aggregation and decision-making power are fundamental issues of the internet-as-we-know-it. Twitter’s persistent neglect of harassment on its platform is one everyday example. It is clear that new protocols and platforms that reduce our dependency on distant power are needed to challenge these issues. What’s less clear, though, is whether or not Urbit actually offers a meaningful alternative. Does Urbit genuinely enable new kinds of relations? Or, does it merely replace the old aristocracy with a new one?

+

+The second, and more urgent, question is: who and what are we supporting by supporting Urbit? Many people in tech still believe that technology can be divorced from its creators; however, those of us in tech need to recognize that we have a considerable amount of influence over which products enter the mainstream consciousness, which products get created at all, and who receives both financial and social capital (shout out to Tech Workers Coalition et al.). For example, consider Peter Thiel , who co-founded PayPal and was an early investor in Facebook. Early support of PayPal and Facebook contributed to their financial success, which developed Thiel’s influence and made him quite rich. Thiel then turned that money and influence into Palantir Technologies, a software company that develops technologies to help expand surveillance and deportation for the government. We have to consider what similar groundwork we help to lay by supporting Urbit.

+

+Context

+

+In order to discuss Urbit’s design, we need to have an understanding of the politics of its creator, Curtis Yarvin. Curtis Yarvin is innocuously described on Wikipedia as an “American political theorist and computer scientist,” but to many, he is better known as one of the intellectual forebears of the alt-right. From 2007 to 2014, working under the pen name Mencius Moldbug, Yarvin writings, which among other things espoused anti-democratic ideas and scientific racism and helped introduce many of what are now understood as the alt-right’s foundational ideologies to a wider public. The term “red pill,” which describes the process of reactionary radicalization and the community around it, was first used in this way by Yarvin. Defenders of Urbit are quick to dismiss any inclusion of Yarvin’s politics in discussions about Urbit as unfair or irrelevant, and might point out that Yarvin left the project in January of this year. However, given that Yarvin basically laid out the general design for Urbit independently, as he worked on it alone for 11 years and in parallel with his political writings, and that Urbit, as a P2P project, is a fundamentally social and thus incorporates ideas about how people should be organized, Yarvin’s politics should be considered as something that influences his design decisions and his long-term vision for the project. Dog-whistles have been identified in some of his writing about Urbit and its design, including his leaning on Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt for questions around Urbit’s governance.

+

+To save space I’ll provide only a very brief overview of Yarvin’s political philosophy—if you like, you can read more about it here, here, here, and here.

+

+Yavin refers to his brand of political philosophy as “neocameralism.” Neocameralism, as described in his essay “Against Political Freedom,” is a political philosophy arguing that state should be run like a business, (i.e., with a CEO at its head and no democratic mechanisms). His ideas are credited as being foundational to the “neoreactionary” movement, which could be described as a neo-monarchist movement (though Yarvin himself doesn’t identify as a “monarchist” because of its association with a constitutional monarchy and not absolute monarchy). In the neoreactionary movement, “divine right” is supplanted with “genetic right” based on scientific racism reframed as “human biodiversity.” Yarvin’s writings are also popular within the right-libertarian sects of Silicon Valley, such as with Peter Thiel (Peter Thiel also has a stake in Tlön, Yarvin’s company which develops Urbit, via Thiel’s VC firm, Founders Fund). The point here is that Yarvin is not a fringe philosopher. His writings have influence over people with considerable power and contributes to the intellectual miasma that emboldens and normalizes anti-democratic, anti-immigrant, misogynistic, and racist policies and attacks.

+

+Urbit

+A self-sovereign internet

+

+Urbit positions itself as infrastructure for self-sovereignty in the digital age, liberating people from ceding control of their data to corporations. The core idea is that Urbit helps you run a personal server that acts as an intermediary between you and other services, including existing services like Facebook (yes, there is a lot more to Urbit—such as its reinvention of parts of the lower-level computational stack—but its P2P layer is what’s of interest here).

+

+Self-sovereignty is an important principle, and I wager that many who regularly use the internet would agree that more of it is valuable for a healthy internet: for being able to control who can access your data, who can and cannot contact you, and so on. But, self-sovereignty is far too vague of a concept on its own. Left- and right-libertarianism both start with self-sovereignty as a core value, but they end up with vastly different conceptions of what meaningful self-sovereignty looks like and how it can be achieved. Left-libertarianism finds that self-sovereignty arises from social organizing, care, and democratic governance, which build towards positive freedoms (freedom to learn, to flourish, and so on); whereas, right-libertarianism believes it comes from the market and that negative freedoms (freedom from restrictions and regulation) are the goal. Though Yarvin does not identify as a libertarian (he is, in his own words, sympathetic to it), his neocameralism is right-libertarianism taken to its logical conclusion of corporate tyranny and serfdom.

+

+To draw an example that you might be familiar with, consider the Twitter-alternative, Gab, which markets itself as a bastion for free speech. Gab, in practice, operates as a niche platform for members of the far-right who have been banned from Twitter: “a haven for white nationalists, neo-Nazis and other extremists”. We might ask then, is Gab a platform for free speech, or is it a platform for hate speech? Who’s speech does Gab prioritize? It quickly becomes clear that the concept of “free speech” that Gab deploys is not quite the same as what others see it to mean.

+

+In a similar way, this slipperiness of self-sovereignty as a concept, especially in light of Yarvin’s political writings, makes me suspicious of what it really means in the context of Urbit. Is Urbit actually designed to give users more autonomy and control? Does it restore any power to internet users?

+

+One central design feature of Urbit is its network hierarchy. As a participant in Urbit, you may be a galaxy (the top of the hierarchy), a star (which fall under galaxies), or a planet (which fall under stars). The description of this hierarchy used to use explicitly feudal metaphors as part of what Yarvin called “digital feudalism,” with himself as the “prince,” and further contributes to my suspicion of Yarvin’s conception of self-sovereignty actually entails.

+

+In trying to backpedal on these naming conventions, Yarvin claims that his ideas about governance are flipped for the internet:

+

+

+ If the real world today is governed as an insanely dysfunctional republic, and the Internet today is governed as a cluster of insanely despotic corporate monarchies, it doesn’t strike me as at all inconsistent with historical thought to treat the former case of misgovernment with efficient monarchism, and the latter case with liberating republicanism.

+

+

+The rationale for why the opposite is the ideal in each case—beyond contrarianism, at least—is unclear. We should dig into how Urbit’s governance is laid out to better understand what’s going on here.

+

+Urbit’s primary governance model is a “self-governing digital republic” where “authority is proportional to property. Galaxies, stars, and planets are conceived of as property to be purchased and in limited supply, and one’s power within Urbit is determined by what tier of ownership they occupy and how much they own. The republic is structured as a “three-chambered legislature balanced against itself,” where galaxies, stars, and planets constitute the three tiers. There is not much detail on how this government would operate, other than an interim constitution, which doesn’t describe how these tiers actually balance each other. For instance, the “planetary assembly”, which manages technical governance, doesn’t have any oversight of the “stellar congress”, which manages internal governance, or the “galactic senate”, which selects consuls, who hold “full authority” in this interim. When it comes to the stars and galaxies, the extent of your political agency as a planet is exit—that is, the only meaningful action you can take is to move to a different host star.

+

+This notion of “exit,” which is popular among Silicon Valley libertarians like Peter Thiel, is a key part of Yarvin’s political philosophy. It is summarized as, in Yarvin’s own words as: “If residents don’t like their government, they can and should move.” Of course, this formulation of mobility as the ultimate form of political action neglects all the actual complications of uprooting yourself (leaving behind friends, family, and history), the question of whether or not any other place will accept you (e.g., in the case of borders or discrimination), and reduces your political expression to a single vote.

+

+Obviously, exit in a digital context is logistically simpler than in a physical one, but it is still not easy. People critical of Twitter’s policies still use Twitter, not because they are hypocritical but because it’s a lot of effort to migrate to a new platform and re-establish connections from the former. People critical of Facebook may remain because it’s the only connection they have to some friends and family members. In both of these cases, having some mechanisms for democratic oversight would be more effective than showing people the door.

+

+There are still further issues with exiting. For example, I may be unable to exit if, perhaps for discriminatory reasons, I cannot find a star that is willing to host me. Or, I may be unable to establish my own star if no one is willing to sell to me for similar reasons. Additionally, we are forced to ask, How bad do things have to get before I decide to exit? Do I just have to endure everything below that threshold? The point of other (democratic) forms of political voice and agency are that they allow us to have a nuanced process of change, one that allows for fundamental shifts as well as the fine-tuning that is inevitably necessary. Limiting one’s political agency to exit, dismisses any potential for incremental change or open discussion—basically, if you don’t like the way things are, you can go. Otherwise, shut up and take it.

+

+Property, ownership, and power

+

+Because “authority is proportional to property” in Urbit, we should look more closely at how ownership is understood and operates in its design. In his farewell, Yarvin, out of ignorance or for rhetorical purposes, does not seem to recognize how ownership is a power relation. This is especially baffling because, as just quoted, in Urbit power and ownership are explicitly linked. Somehow in Yarvin’s broader understanding of things, property ownership is “random” and this means we should just let it be:

+

+

+ When you live in Manhattan, you simply don’t worry about who owns it or why; and nor does it matter. Are they Jews? Muslims? Christians? Communists? Italians? You don’t care and you don’t have to. You know it’s basically random and probably unfair. Randomness, even blatant unfairness, creates a kind of neutral, peaceful, even promising urban anonymity.

+

+

+However, contrary to Yarvin’s claims, who owns what in Manhattan matters to a great many people. With apartments left vacant to be used as investment vehicles, or else in low-use because it’s more profitable to rent them out as Airbnbs, many people are rightfully critical of who owns (and profits) from these properties—properties that could, among other things, serve to house some New York’s homeless population. Likewise, people are critical of how the developers who own large portions of the city use their positions to lobby state government to compound and expand their influence. Whether or not the current allocation of Manhattan’s space is random (how developers lobby local government is a clear example that it’s not) or unfair does not mean we should throw up our hands and let it be. This line of argumentation is a red herring to deter questioning the property-power dynamics that undergird Urbit’s design.

+

+If power in Urbit is predicated on ownership, then it’s worth asking who owns what. The distribution of galaxies (as of 2016 at least) puts 185 of the 256 in the hands of Tlön, Tlön’s employees, and urbit.org (which is currently under management and ownership of Tlön). The story for stars is not much different: 57.62% of stars (almost 38,000 of the 65,500 stars) are also owned by Tlön, its employees, and urbit.org. Even with Urbit’s tiered hierarchical structure, which ostensibly decentralizes power, we can see that power is quite concentrated (which they acknowledge).

+

+This comparison to Manhattan calls back to Urbit developers’ comparison of their system to land. Urbit’s design creates a class of digital landlords who are the primary political authorities. There are obviously significant differences between physical land and digital space, but it strikes me as a regression to reproduce land scarcity (and rent-seeking structures) in cyberspace. For Urbit’s digital land, scarcity has to be manufactured, and manufactured digital scarcity seems antithetical to P2P values—where the easy replicability of data represents new opportunities and alternatives to the crude economies we’ve stumbled through in the physical world.

+

+How then does Urbit justify this manufactured scarcity? The primary reason is as a defense against Sybil attacks—a class of attacks endemic to pretty much any digital networking system where adversaries can generate identities in bulk to attack the system (e.g., DDoS attacks or spam). Spam is something like a Sybil attack—it’s easy to make tons of email addresses and use them to bombard people.

+

+The paper that introduced Sybil attacks proved that there is no way to altogether prevent such attacks without introducing a centralized identity-verification authority. In the case of spam this would be like one organization that manages a global registry of non-spam emails. There are, however, ways to make Sybil attacks more expensive and thus less feasible to execute. In the case of Urbit, the scarcity is meant to compel prices for stars and planets such that they are too expensive for an attacker to purchase in bulk.

+

+There are other decentralized Sybil-defense schemes proposed for P2P networking. Some introduce cryptographic puzzles, similar to Bitcoin’s proof-of-work. Others are based on explicit trust in social networks. These approaches aren’t without their flaws—Sybil attacks can’t be completely prevented, after all—but, crucially, these schemes don’t introduce points of centralization that require concentrated trust or introduce authorities that can exclude non-adversarial actors from the network. Because Urbit’s supply is explicitly controlled by owners of galaxies and stars, they can deny people access for any arbitrary reason. This is especially concerning because of the aforementioned concentration of Urbit property.

+

+Yet even though Urbit’s design grants political power proportionally to ownership, “[f]or the interim, full authority is held by the (Roman style) consulate.” Urbit is functionally an authoritarian regime for now. It is designed to decentralize eventually—Urbit documentation acknowledges a need to spread out ownership of its assets. But, given the initial distribution of galaxies—95 galaxies to the Tlön Corporation; 50 to urbit.org (the future community foundation); 40 to Tlön employees and their family members (24 to Yarvin, who started in 2002, and 16 to everyone else who started in 2014); 34 to outside investors in Tlön; and 37 galaxies to 33 other individuals, who donated to the project, contributed code or services, won a contest, or were just in the right place at the right time—it isn’t clear what kind of further distribution of ownership they have in mind, or even whether it will be meaningful. More troubling still is that in their own words, Urbit describes this distribution as being spread “across a diverse set of entities,” when it seems to only encompass people in their immediate networks. This arrangement is reminiscent of Manhattan real estate: the earlier you got in, the more ownership, and thus power, you accrued.

+

+Furthermore, “decentralization” when used to describe governance is notoriously slippery, especially in blockchain and blockchain-adjacent contexts such as P2P. What does it mean for a government to be meaningfully decentralized? If galaxies and stars become prohibitively expensive to the point where only the wealthy can purchase them, does that lead to a decentralized government? Decentralization also says nothing about representative ratios. In the US, we have 535 members of Congress representing 320 million Americans; if Urbit achieves full adoption, there’ would be 256 galactic senate members representing 4.3 billion planets.

+

+There’s nothing to suggest that Urbit even cares about how representative its governance structures are. The word “democratic” is scarce across descriptions of Urbit’s governance. “Democracy” only appears once throughout all of urbit.org, and it is in a sarcastic quote. The term also appears in an older document, and its use is telling: “Urbit will never be a democracy, but it should always remain a republic.” In that same document, Yarvin does mention that the dukes (now “galaxies” in the new terminology) will be organized democratically, but this is consistent with the republic formulation.

+

+This, combined with Yarvin’s admiration of the Roman Principate as an example of a government that “retain[s] the symbolic structures of democracy” while being autocratic in practice (the Roman Principate was ruled by an emperor but maintained a superficial senate for the appearance of a continuing republic), gives me reason to doubt the intentions around governance here. A new internet under this regime could easily turn out to be just as bad as or worse than it is now.

+

+Who Urbit Supports

+

+While Yarvin is officially removed from the further design and development of Urbit, he still maintains a minority share in Tlön and a few thousand stars (he is “probably the only individual with a fair amount of Urbit address space”). His departure at this point is not enough to counteract his heavy, and at times exclusive, involvement in Urbit’s foundational design and development.

+

+For me, there is an issue that goes beyond Urbit’s design and future ambitions. It comes down to the fact that if I were to support Urbit, I would also be supporting Yarvin—he still has a substantial stake in its success and, like any network-based platform, the value of Urbit increases the more people use it. At least some people do support Urbit because they support Yarvin’s politics. Yarvin’s years writing as Mencius Moldbug were possible because of money made during the dot-com boom. After announcing his departure, people have expressed excitement around his return to writing, so we may see further works of political philosophy from him. Even if Yarvin were to never write again, the success of Urbit is likely to draw attention to its creator—and introduce more people to his past writings.

+

+Beyond introducing Yarvin’s writings to new audiences, we should also consider how supporting Urbit supports Yarvin more directly. We can get a rough sense of Yarvin’s financial stake in Urbit, leaving aside speculation about his financial stake in Tlön itself:

+

+There are 256 galaxies and 65,536 stars across all of Urbit. There are roughly 4.3 billion planets that were initially evenly distributed across stars, so each star started with 65,000 planets. In the long-run Urbit developers believe $10 to be a fair price for a planet. Assuming that the price eventually converges to $10 per planet and Urbit achieves widespread adoption, then each star is worth $650k in planet real estate alone. Planets are also expected to pay a monthly fee to their stars for routing services (which is the bare minimum service; the star may choose to offer services as well). This fee is estimated to be anywhere from $10–$100 per month.

+

+Let’s assume the lower end, that $10/month is required for the routing services. If a star sells all of its planets and they remain under that star, that’s potentially another $650k in revenue per month. When we consider that Yarvin owns “a few percent of all stars” (which is thousands of stars), if Urbit does achieve widespread adoption, then that is a staggering amount of wealth. Yarvin’s nominal departure from Urbit does not change the fact that he stands to gain tremendously from its success.

+

+What does an internet in which Urbit achieves widespread adoption look like? I’m not sure it would look much different. You would have a personal server, sure; but then there would then be a new infrastructural layer between you and your ISP (who you’ll still have to pay) owned by another class of rentiers who you’ll also pay. One of the great appeals of P2P is that routing occurs almost as a side-effect of everyone using the internet, so by being online, you help others be online at essentially no additional cost. Urbit abandons this P2P property of mutual aid such that the property and power relations of the internet are mostly kept intact.

+

+Of course, it’s not certain—or even likely—that Urbit will ever achieve this level of adoption and value. What is clear, however, is that if I were to support Urbit, then I would, even in a small way, be making its spread and adoption all the more likely. We already spend so much of our time and money supporting regimes of violence, oppression, and inequality by merely existing in a capitalist society. These relationships are hard to break because they are so deeply established and entrenched within culture and the market. Urbit is not yet entrenched in the same way, and I do not want to help it get there. I want to have no part in supporting Yarvin or any other project or creator whose underlying ideology is hateful, reactionary, or anti-democratic.

+

+Closing Words

+

+Urbit is still in such a nascent state with much left ambiguous. Its value (or your expectations of its value) largely depends on how much you trust the people behind it. It’s hard for me to trust people who have no problem working for someone like Yarvin who has actively contributed to the re-emergence of white supremacy and anti-democratic ideas, or who would go so far to dismiss Yarvin’s Nazi apologia (“What’s so bad about Nazis?”) as “trolling.”

+

+“Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” the Borges story where Yarvin’s company gets its name, describes a secret society, Orbis Tertius, that architects an entirely new world, Tlön, by publishing an encyclopedia describing it. Over time, bits of this fictional world begin to emerge in the real world, consuming it, such that “[t]he world will be Tlön.” What ideas are Yarvin’s Tlön trying to manifest in our world? What world would Yarvin seek to manifest with his new wealth?

+

+In asking these questions, we should consider them not only as tools for evaluating similar projects but also as criteria with we might develop new projects. What ideas do we want to manifest in our world? I absolutely agree that what Urbit positions itself against—an internet dominated by concentrated corporate interests and surveillance infrastructure—is something that internet technologists need to build alternatives to. But we shouldn’t replace it with another system of undemocratic control or one that supports far-right intellectuals. I hope to see more P2P projects that commit to most promising values of P2P systems—plurality, democracy, mutual interdependence, sharing, and cooperation—as they take on the difficult but necessary task of creating egalitarian platforms and infrastructure, rather than rehashing the old hierarchies. P2P computing is still a burgeoning technology, and while there are projects like Scuttlebutt, Beaker Browser, and the various Fediverse projects, which all reflect its potential, there is plenty of room for more.

+

+Additional acknowledgements: thanks to Dan Taeyoung and Matt Goerzen for their comments and insights.

+

+About the Author:

+

+

+Francis Tseng in an engineer working primarily with simulation and machine learning. His research interests include climate change, tech autonomy, and traps. He is currently a fellow at the Jain Family Institute. Formerly, he taught at the New School and co-published The New Inquiry.

+

+]]>

+

+

+

+ +

+ +

+

+

+