The aim of Born2beRoot is to learn and explore the fundamentals of system administration and virtualization by inviting us to install a virtual machime using VirtualBox.

We have to create a server respecting the partition scheme defined in the subject, and we have the right to choose between two Linux distributions (Debian or Rocky).

Here you can find the topics that we will examine, we are going to tackle the configuration of the server, I will not go through the installation.

-

- What is a Virtual Machine?

- Advantages of a Virtual Machine

- Types of virtuallization

-

- What is LVM?

- LVM components

- What is encryption?

- Purpose of sevaral partitions

-

- What is a File System?

- Types of file systems

- Directory Structure

- What is Mounting?

-

- What is sudo?

- Installing sudo

- Configuring sudo

-

- APT

- Aptitude

- The diffrence between APT & Aptitude

-

- What is UFW?

- IP Addresses & Ports

- Installing & Configuring UFW

-

- What is SSH?

- How does SSH works?

- Installing & Configuring SSH

- Port Forwarding in VirtualBox

-

- Changing hostname

- User Management

- Group Management

-

- The script

- The Wall Command

- The Cron Service

-

What is a Virtual Machine:

A virtual machine (VM) is a software emulation of a computer system. It operates based on the architecture and functions of a real or physical computer. VMs run applications and operating systems just like a physical computer. They allow multiple virtual machines to run on a single physical machine, sharing its resources such as CPU, memory, and storage. This enables efficient utilization of hardware and provides flexibility and isolation for running different operating systems and applications. -

Advantages of a Virtual Machine:

Resource Efficiency:VMs allow multiple operating systems to run on a single physical machine, sharing resources efficiently.

Isolation:Each VM operates independently, which means that issues in one VM do not affect others.

Flexibility:VMs can be easily created, modified, or deleted without impacting the host system or other VMs.

Testing and Development:VMs provide a safe environment for testing new software or configurations without risking the host system.

Disaster Recovery:VMs can be backed up and restored quickly, which is crucial for business continuity and data recovery.

Scalability:VMs can be easily scaled up or down to meet changing demands.

Cost Savings:By consolidating multiple servers onto a single physical machine, VMs can reduce hardware costs.

Portability:VMs can be moved between different physical machines with minimal disruption. -

Types of virtuallization:

There are two main types of virtualization:

1. Hardware Virtualization:Also known as Bare Metal, this involves creating a virtual version of an entire computer system, including the hardware. It allows multiple operating systems to run on a single physical machine, each with its own virtual hardware.

2. Operating System Virtualization:This involves running multiple isolated instances of an operating system on a single host, sharing the host's kernel but having separate user spaces. Containers are more lightweight than VMs and are often used for deploying applications. -

System Administration:

System administration is the practice of managing and maintaining computer systems, networks, and services. It involves a variety of tasks, including:

Installing and configuring hardware and software.

Managing user accounts and permissions.

Ensuring system security and compliance with policies.

Monitoring system performance and availability.

Troubleshooting and resolving technical issues.

Planning for system growth and capacity.

Keeping systems up-to-date with the latest patches and updates.

Sstem administrators are responsible for the smooth operation of IT infrastructure and are often the first point of contact for technical issues within an organization.

-

What is LVM:

LVM, or Logical Volume Management, is a method of disk management that allows for the flexible allocation of disk space to logical volumes. Unlike traditional disk partitioning, which divides a physical disk into fixed-size partitions, LVM allows for the creation of logical volumes that can span multiple physical disks. This flexibility enables easier disk space management, including resizing, moving, and snapshotting of volumes. -

LVM components:

Here's a brief overview of LVM components and concepts:

1. Physical Volumes (PVs):These are the actual physical disks or partitions that are used by LVM. They are the lowest level of storage in LVM.

2. Volume Groups (VGs):A volume group is a collection of one or more physical volumes that are combined to form a single logical unit. VGs are used to allocate disk space to logical volumes.

3. Logical Volumes (LVs):These are the virtual partitions created within a volume group. They can be resized, moved, and snapshotted independently of the physical storage.

4. Physical Extents (PEs):The smallest unit of disk space that can be allocated to a logical volume. A physical volume is divided into physical extents, which are then used to create logical volumes.

5. Snapshots:LVM allows for the creation of snapshots of logical volumes. A snapshot is a point-in-time copy of a logical volume, which can be used for backup or testing purposes.

6. Striping:LVM supports striping, which is the process of splitting data across multiple physical volumes to improve performance. This can be done at the volume level or within a single logical volume.

7. Mirroring:LVM can also mirror data across multiple physical volumes to provide redundancy and improve data integrity. -

What is encryption:

Encryption is the process of converting plain, readable data into an unreadable format using algorithms and keys. This is done to secure the data and prevent unauthorized access, ensuring that only authorized parties with the corresponding decryption keys can access and understand the original information.

Based on the subject, when configuring volumes in Linux, particularly with Logical Volume Manager (LVM), the encryption is typically achieved using a software-based encryption mechanism called dm-crypt. dm-crypt is a kernel-level encryption module that provides transparent encryption of block devices, including logical volumes managed by LVM. -

Purpose of sevaral partitions:

We could very well have a single partition to contain all of the operating system’s data, all of the software and all of the personal user files. The purpose of having several distinct partitions is to not put all our eggs in the same basket. If one file system becomes corrupted for example, only one of the partitions would be affected instead of the entire system.

In summary, the utilization of multiple partitions provides advantages such as organization, security, multi-boot capability, performance optimization, backup efficiency, and file system flexibility.

-

What is a File System:

In Linux, a file system is a method of storing and organizing files on a storage device, such as a hard disk, solid-state drive, or network storage. It defines how data is stored, retrieved, and managed on the device. The file system is responsible for keeping track of files, directories, and the space on the disk. It provides a structure that allows users and applications to read from and write to files in a way that is efficient and organized. -

Types of file systems:

Linux supports a variety of file systems, each with its own set of features and capabilities. Some of the most commonly used file systems in Linux includes:

ext, ext2, ext3 and ext4:The file system Ext stands for Extended File System. It was primarily developed for MINIX OS. The ext file system is an older version, and is no longer used due to some limitations.

Ext2 is the first Linux file system that allows managing two terabytes of data. Ext3 is developed through Ext2; it is an upgraded version of Ext2 and contains backward compatibility. The major drawback of Ext3 is that it does not support servers because this file system does not support file recovery and disk snapshot.

Ext4 file system is the faster file system among all the Ext file systems. It is a very compatible option for the SSD (solid-state drive) disks, and it is the default file system in Linux distribution.

FAT32 and NTFS:These are file systems commonly used in Windows environments but can also be used in Linux for compatibility with removable storage devices.

JFS:JFS stands for Journaled File System, and it is developed by IBM for AIX Unix. It is an alternative to the Ext file system. It can also be used in place of Ext4, where stability is needed with few resources. It is a handy file system when CPU power is limited.

Swap:The swap file system is used for memory paging in Linux operating system during the system hibernation. A system that never goes in hibernate state is required to have swap space equal to its RAM size.

etc.:There is much more to filesystems, if you want to dive deeper, here is a good source.In summary, you can say that a filesystem serves as a signal or a "flag" to the operating system, indicating which driver to load for reading and writing data on a specific drive or partition.

-

Directory Structure:

The Linux directory structure is a hierarchical organization of files and directories that defines how data is stored and accessed on a Linux system. It's designed to make it easy for users and applications to find and access files. Here's a brief overview of the main directories in the Linux filesystem:

/:The root directory, is the top-level directory in the hierarchy. All other directories and files on the system are contained within this directory.

/bin:Contains essential command binaries that are needed for the system to boot and run. These are basic commands that are available to all users.

/sbin:Similar to /bin, but contains system binaries that are typically used for system maintenance and administration.

/etc:Contains system-wide configuration files. This directory is crucial for the configuration of the system and its services.

/home:Contains user directories. Each user has a directory under /home where their personal files and directories are stored.

/usr:Contains multi-user utilities and applications. This includes binaries, libraries, and documentation.

/var:Contains variable data files such as system logs, databases, and mail. This directory can grow in size over time.

/tmp:A temporary directory used for storing temporary files created by the system and users.

/boot:Contains files needed to boot the system, including the Linux kernel and initial RAM disk (initrd).

/dev:Contains device files that represent hardware devices. These files are used by the system to interact with hardware.

/proc:A virtual filesystem that provides information about the system and running processes.

/srv:Contains site-specific data served by your system.

/mnt and /media:Used for mounting external file systems. -

What is Mounting:

Mounting in Linux is the process of making a file system available for use by attaching it to a specific directory in the existing file system hierarchy. This allows users and applications to access the files and directories on the mounted file system as if they were part of the main file system. The mount command is used to perform this operation, specifying the device and the mount point. -

What is sudo?

sudo stands for "superuser do" is a command in Linux that allows a permitted user to execute a command as the superuser or another user, as specified by the security policy. The sudo command is used to perform administrative tasks that require elevated privileges, such as installing software, modifying system files, or changing system settings. -

Instaling sudo:

In order to install sudo, first we need to login as root.# su root <enter the root password> # apt update # apt upgrade # apt install sudoNow, we need to give our regular user the ability to use sudo, by adding the user to the sudo group (and checking that it was added successfully).

# sudo usermod -aG sudo <username> # getent group sudoTo check if we now have sudo privileges, we can

exitthe root session to go back to our own user, then run the following command:# sudo whoami <enter password> rootOnce our password entered, we should get, as an answer,

root. If that doesn’t work, we might have to logout and log back in for the changes to take effect.

As a very last resort, if the user still has no sudo privileges after logging out and back in again, we will have to modify thesudoers.tmpfile from the root session with the following commands:# su # sudo visudoAnd add this line to the file:

<username> ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL -

Configuring sudo:

For security reasons, the Born2beroot subject requires a few more sudo configurations. We must:- Limit authentication for sudo to 3 tries for a bad password.

- Define a custom message in case of a bad password.

- Log sudo commands in

/var/log/sudo/. - And activate TTY to stop malicious software from giving itself root privileges via sudo.

In order to do this, we need to add the following lines to the sudoers.tmp file (as above, we must open it from the root session, with the sudo visudo command to be able to write changes to it):

Defaults passwd_tries=3

Defaults secure_path="/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/snap/bin"

Defaults badpass_message="Wrong password. Try again!"

Defaults logfile="/var/log/sudo/sudo.log"

Defaults log_input

Defaults log_output

Defaults requirettyDefaults log_output not saving the output, how I got around this, by adding the line Defaults iolog_dir="/var/log/sudo". Now the output of sudo command will be archived at /var/log/sudo/00/00, and each command would be indexed with a hexadecimal nunber. You can used the zcat command on ttyout file to display the output.

If the /var/log/sudo directory doesn’t exist, we might have to mkdir sudo in /var/log/.

Now, we can have root privileges in secure way, without having to log into the root session.

In Linux-based operating systems such as Debian, software installation is achieved through packages. These packages encapsulate all the necessary files required for executing a specific set of commands or functionalities. Thus, it's crucial to understand how to install these packages on our Born2beroot virtual machine.

-

APT:

APT (Advanced Package Tool) is a package management command-line tool used by Debian. It simplifies the process of managing software packages on Linux systems. apt provides a high-level command-line interface for the package management system and is designed to handle the installation, upgrade, and removal of software packages, as well as the management of package dependencies.

Here are some of the key functionalities provided by apt:

Installing Packages:You can install new software packages using theapt installcommand.

Updating Package Lists:Before installing new packages, it's a good practice to update the package lists to ensure you're getting the latest versions. This is done with theapt updatecommand.

Upgrading Packages:To upgrade all installed packages to their latest versions, you can use theapt upgradecommand.

Removing Packages:If you no longer need a package, you can remove it using theapt removecommand.

Searching for Packages:You can search for available packages using theapt searchcommand.

Cleaning Up:apt also allows you to clean up unnecessary packages and dependencies that were installed as dependencies but are no longer needed with theapt autoremovecommand. -

Aptitude:

Aptitude also like APT, it's a high-level package management interface for Debian-based systems, it provides a text-based interface similar to a menu-driven package manager, making it more user-friendly for some users who prefer graphical interfaces. Aptitude can perform most package management tasks, including installing, removing, and upgrading packages, as well as searching for packages and resolving package dependencies. Aptitude also includes features like package filtering, package previewing, and a powerful dependency resolver. -

The diffrence between APT & Aptitude:

Interface:APT primarily offers a command-line interface, whereas Aptitude provides a text-based menu-driven interface.

Functionality:Both tools can perform similar package management tasks, but Aptitude may offer additional features like package filtering and previewing.

User Experience:Aptitude may be preferred by users who are more comfortable with graphical or menu-driven interfaces, while APT may be preferred by those who prefer command-line interfaces.

Resource Usage:Aptitude tends to use slightly more system resources compared to APT due to its interactive interface and additional features.

In summary, both APT and Aptitude are powerful package management tools in Debian-based Linux distributions, each with its own set of features and interface preferences. Users can choose the tool that best fits their needs and workflow.

AppArmor is a Linux security module that restricts the capabilities of individual programs by enforcing security policies, ensuring that programs can only perform actions that are explicitly allowed. It come preinstalled in Debian.

AppArmor uses profiles to define the security policies for each program. A profile is a set of rules that specify what actions a program can perform and on which files or directories. Profiles are stored in the /etc/apparmor.d/ directory.

Apparmor has two types of profile modes, enforced and complain. Profiles in enforcement mode enforce that profile's rules and report violation attempts in /var/log/syslog. Profiles in complain mode don't enforce any profile rules, just log violation attempts.

The apparmor-utils package contains command line tools for configuring Apparmor. Using it you can change Apparmor's execution mode, find the status of a profile create new profiles, etc.

These are the most common commands:

- You can check Apparmor's status with

aa-status. - To put a profile in

complainmode you can usesudo aa-complain /path/to/profile,</path/to/profile>path where the profile directory is located. - To put a profile in

enforcedmode you can usesudo aa-enforce /path/to/profile. - You can read more over here.

- What is UFW:

UFW, or Uncomplicated Firewall, is a user-friendly front-end for managing iptables firewall rules in Linux. It simplifies the process of configuring a firewall, making it easier for users to set up and manage firewall rules without needing to understand the complexities of iptables directly. UFW is designed to be straightforward and easy to use, making it a popular choice for managing firewall settings on Linux systems. - IP Addresses & Ports:

When we talk about traffic and networks, we must understand to things; IP addresses and ports.

An IP address is a unique identifier assigned to each device connected to a network, allowing it to communicate with other devices. It can be either IPv4 (Internet Protocol version 4) or IPv6 (Internet Protocol version 6), with IPv4 being the most commonly used format.

A port is a communication endpoint in a computer's networking stack. It allows a computer to distinguish between different types of traffic and to manage multiple connections to the same IP address. Ports are identified by numbers, with the range from 0 to 65535. Common port numbers include 80 for HTTP traffic, 443 for HTTPS, and 22 for SSH. Together, an IP address and a port number form a socket, which is used to identify a specific process or service on a device. This combination allows multiple services to run on the same device, each accessible via a unique combination of IP address and port number. - Installing & Configuring UFW:

As the subject suggests the firewall must be active when you launch your virtual machine.To check if UFW up and running we can use the command line:$ sudo apt update $ sudo apt upgrade $ sudo apt install ufw $ sudo ufw enableWe should see “active” in green.$ sudo systemctl status ufw

Also we have to leave only port 4242 open.To delete any uneseserry rules, you can list all available rules with the command line:$ sudo ufw allow 4242And then delete them with the$ sudo ufw status numbereddeleteplus the rule's index:$ sudo ufw delete 2

- What is SSH?

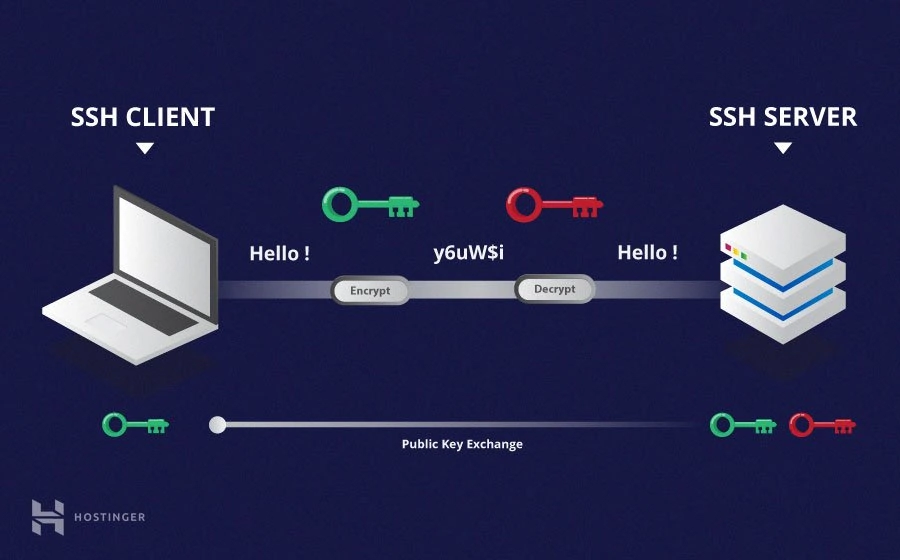

SSH (Secure Shell) is a cryptographic network protocol used for secure communication over an unsecured network. It provides a secure way to access and manage remote systems or devices over a network, such as the internet. SSH is commonly used for tasks like remote command execution, file transfer, and tunneling network connections. - How does SSH works?

SSH commonly uses asymmetric encryption as part of its authentication process. Asymmetric encryption, also known as public-key cryptography, works with a pair of cryptographic keys: apublic keyand aprivate key.

The public key is used to encrypt data, while the private key is used to decrypt it. Messages encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the corresponding private key, ensuring secure communication without the need to share secret keys.

-

You can read more over here.

-

Installing & Configuring SSH:

In Born2beroot, we are asked to install this protocol and route it trough the 4242 port. OpenSSH is the most popular and widespread tool, so let’s install that one. Since we want to be able to connect to our Born2beroot machine from another machine, we need the openssh-server packet. In order to connect to another machine from the Born2beroot machine, we would need the openssh-client packet.

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt upgrade

$ sudo apt install openssh-server

$ sudo systemctl enable ssh.serviceTo check SSH is up and running we can use the command line:

$ sudo systemctl status ssh.service

We should see “active” in green.

Now we need to modify the ports that SSH is listening to, that can be done by editing the ssh configuration file:

$ sudo nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

The line we are looking for is towards the beginning of the file and reads “#Port 22”. We want to uncomment that and change it to “Port 4242”

...

Include /etc/ssh/sshd_config.d/*.conf

Port 4242

#AddressFamily any

...Also the jubject mentioned "For security reasons, it must not be possible to connect using SSH as root.", for that we can uncomment the rule PermitRootLogin and set it to no.

...

# Authentication:

#LoginGraceTime 2m

PermitRootLogin no

#StrictModes yes

...Then, we have to restart the ssh service for the change to take effect.

$ sudo systemctl restart ssh

If you want to generaye your public & private keys you can use the command ssh-keygen.

Let’s not forget to tell our firewall to authorize the 4242 port connection! We might also have to delete a new rule about Port 22 which was added automatically with OpenSSH’s installation.

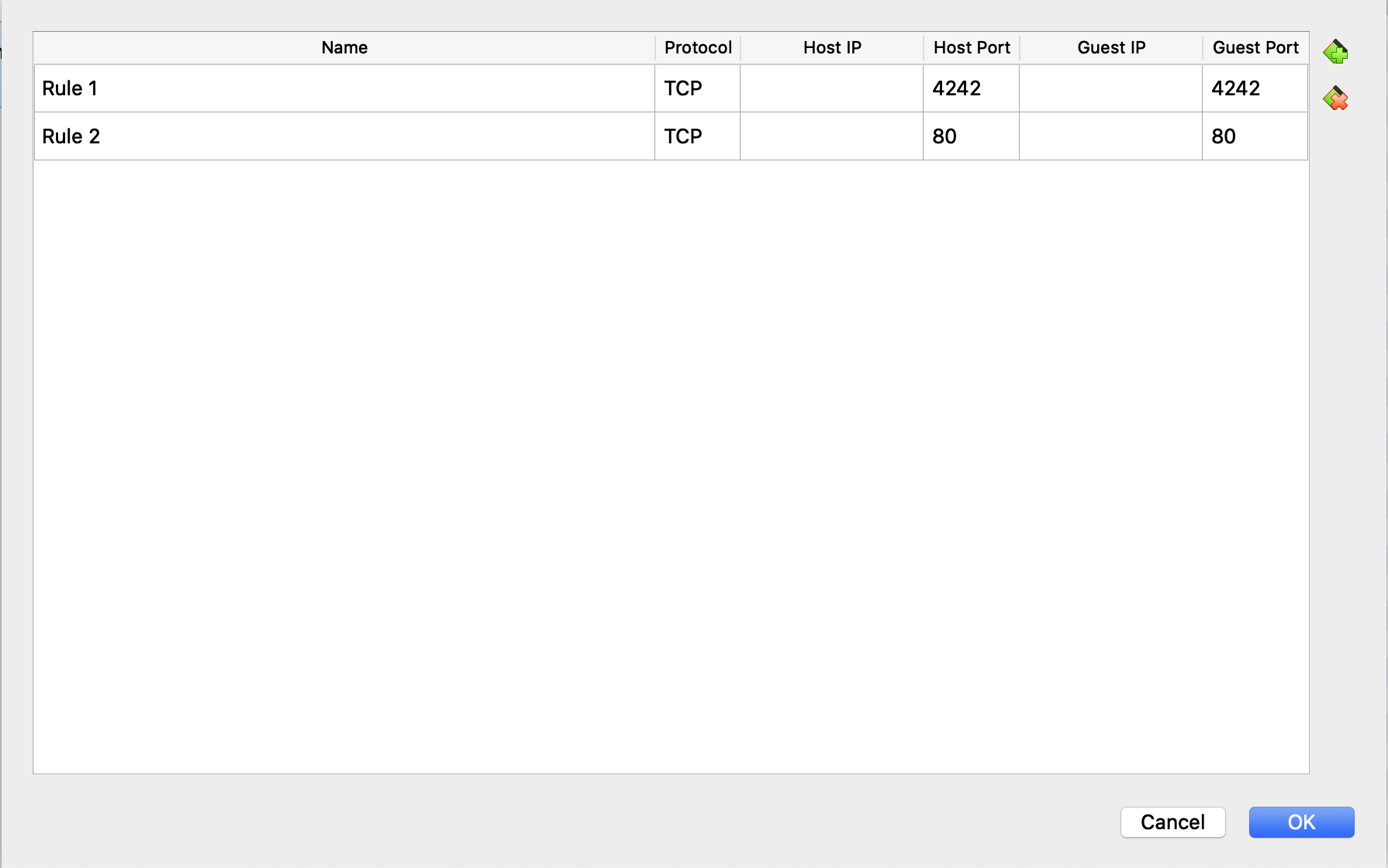

- Port Forwarding in VirtualBox:

Before we can connect to the virtual machine from another computer via SSH, we have to make a little adjustment in VirtualBox. Indeed, the connection will be refused until we forward the host port to the VM port.

In VirtualBox, select the Born2beroot machine and go into configuration settings.

$ sudo systemctl restart ssh

$ sudo systemctl status ssh

- Logging into the Born2beroot Server via SSH:

Now that we have configured everything, we can check the SHH connection by attempting to log into the Born2beroot virtual machine from the host machine terminal. Of course, the virtual machine must be turned on to be able to connect to it.

From the host machine’s terminal, we can connect via SSH with this command:

$ ssh <username_server>@<server_IP_address> -p <ssh_port>

The username will of course be that of the virtual machine user and the port will be 4242. But what is the IP address of our Born2beroot server? Since the virtual machine shares the host’s IP address, we can simply use the localhost IP address. Localhost is an internal shortcut that every computer uses to refer to their own IP address. The localhost IP is 127.0.0.1.

So we can transcribe the previous command in one of the two following ways:

$ ssh <user>@localhost -p 4242

or

$ ssh <user>@127.0.0.1 -p 4242

<enter user passwor>

Once we enter the user password, we can control the virtual machine from the outside! Let’s note that the command prompt has changed and now shows the virtual machine’s hostname.

In order to put an end to the SSH connection, all we need to do is:

exit

- The subject consist of having a strong password policy, we have to implement the following reguirement:

- Your password has to expire every 30 days.

- The minimum number of days allowed before the modification of a password will be set to 2.

- The user has to receive a warning message 7 days before their password expires.

- Your password must be at least 10 characters long. It must contain an uppercase letter, a lowercase letter, and a number. Also, it must not contain more than 3 consecutive identical characters.

- The password must not include the name of the user.

- The following rule does not apply to the root password: The password must have

at least 7 characters that are not part of the former password.

In order to configure the first 3 rules, we have to edit the/etc/login.defsfile:

sudo nano /etc/login.defs

And find the “Password aging controls” section to change the values such that:

PASS_MAX_DAYS 30

PASS_MIN_DAYS 2

PASS_WARN_AGE 7However, these changes will not automatically apply to preexisting users. For both root and our first user, we need to use the chage command to enforce these rules. The -l flag is available to display which rules apply to a certain user.

$ sudo chage -M 30 <username/root>

$ sudo chage -m 2 <username/root>

$ sudo chage -W 7 <username/root>

$ sudo chage -l <username/root>

For the rest of the rules, we will have to install the password quality verification library.

$ sudo apt install libpam-pwquality

Then, we must edit the /etc/security/pwquality.conf configuration file. Here, we will need to remove the comment sign (#) and change the values of the various options. We will end up with something like this:

# Number of characters in the new password that must not be present in the

# old password.

difok = 7

# The minimum acceptable size for the new password (plus one if

# credits are not disabled which is the default)

minlen = 10

# The maximum credit for having digits in the new password. If less than 0

# it is the minimun number of digits in the new password.

dcredit = -1

# The maximum credit for having uppercase characters in the new password.

# If less than 0 it is the minimun number of uppercase characters in the new

# password.

ucredit = -1

# ...

# The maximum number of allowed consecutive same characters in the new password.

# The check is disabled if the value is 0.

maxrepeat = 3

# ...

# Whether to check it it contains the user name in some form.

# The check is disabled if the value is 0.

usercheck = 1

# ...

# Prompt user at most N times before returning with error. The default is 1.

retry = 3

# Enforces pwquality checks on the root user password.

# Enabled if the option is present.

enforce_for_root

# ...And that’s all there is to it!

- Changing hostname:

We can change the hostname with the following command:

$ sudo hostnamectl set-hostname <new_hostname>

We could also change the hostname by editing the files /etc/hostname & /etc/hosts instead.

You need to restart the machime for changes to take effect.

-

User management:

For the evaluation, we must be able to show a list of all users, add or delete user accounts, change their usernames, add or remove them from groups, etc. The following commands are necessary to do all of that:

useradd <username>: creates a new user.

usermod <username>: changes the user’s parameters:-lfor the username,-cfor the full name,-gfor groups by group ID.

userdel -r <username>: deletes a user and all associated files.

id -u <username>: displays user ID.

users: shows a list of all currently logged in users.

cat /etc/passwd | cut -d ":" -f 1: displays a list of all users on the machine.

cat /etc/passwd | awk -F ":" '{print $1}': same as above. -

Group Management:

In the same way, we will have to manage user groups. Our default personal user must be in thesudoanduser42groups. The following commands need to be mastered for the evaluation:

groupadd: creates a new group.

gpasswd -a: adds a user to a group.

gpasswd -d: removes a user from a group.

groupdel: deletes a group.

groups: displays the groups of a user.

id -g: shows a user’s main group ID.

getent group: displays a list of all users in a group.

- The script:

The last thing we have to do for mandatory part is a bash script namedmonitoring.sh, it must display the following information every 10 minutes broadcasted on evey terminal connected to our virtual machine:- The architecture of your operating system and its kernel version:

# uname --all- The number of physical processors.

# lscpu | grep 'Socket(s)' | awk '{print $2}'- The number of virtual processors.

# lscpu | grep 'Core(s)' | awk '{print $4}'- The current available RAM on your server and its utilization rate as a percentage.

# free --mega | grep 'Mem' | awk '{print $3"/"$2"MB"}' # free --mega | grep 'Mem' | awk '{printf "%.2f%%\n", $3 / $2 * 100}'- The current available memory on your server and its utilization rate as a percentage.

# df -h --total | grep 'total' | awk '{print $3 "/" $2}' # df -h --total | grep 'total' | awk '{printf "%.2f%%\n", $3 / $2 * 100}'- The current utilization rate of your processors as a percentage.

# mpstat | grep 'all' | awk '{print 100 - $13"%"}'- The date and time of the last reboot.

# who -b | awk '{print $3 " " $4}'- Whether LVM is active or not.

# if [ $(lsblk | grep 'lvm' | wc -l) == 0 ]; then echo "No"; else echo "Yes"; fi- The number of active connections.

# netstat -t | grep 'tcp' | wc -l- The number of users using the server.

# who | awk '{print $1}' | sort -u | wc -l- The IPv4 address of your server and its MAC (Media Access Control) address.

# echo "IP " && hostname -I && ip link | grep 'link/ether' | awk '{printf "(%s)", $2}'- The number of commands executed with the sudo program.

# grep 'COMMAND' /var/log/sudo/sudo.log | wc -l && echo "cmd"

NOTE

# chmod 755 monitoring.sh

The command mpstat is defined on sysstat package, also as the command netstat on net-tools.

# apt install sysstat

# apt install net-tools

-

The Wall Command:

The wall command in Linux is used to broadcast a message to all users currently logged into the system. It sends a message to all terminals, including those that are idle or inactive. This can be useful for system administrators to communicate important information or announcements to all users at once.

Example:# echo "System will be rebooted in 10 minutes. Please save your work." | wall or # wall "System will be rebooted in 10 minutes. Please save your work." -

The Cron Service:

Cron is a program that enables the execution of scripts or software in an automatic way, at a certain date and time or at a specified interval. It is installed by default in Debian (we can check this with theapt list croncommand). To be certain it will run at system startup, we should enable it:# systemctl enable cronCron uses crontab files to schedule jobs. Each user can have one, or many. As the root user, we will now create one with the following command:

# crontab -eThe syntax of a cron file might seem obscure, but it’s not too hard to wrap your head around:

* * * * * <command to execute>here is what each star represents:

.------------------------ minutes (0-59) | .-------------------- hours (0-23) | | .---------------- day of the month (1-31) | | | .------------ month of the year (1-12) | | | | .-------- day of the week (0-6, 0 = sunday) | | | | | * * * * * <command to execute>By replacing the stars with numerical values, we can define when our command must be executed.

So is this the way we should write “every 10 minutes”?10 * * * * bash /root/monitoring.shAlmost, but no. This instruction means “execute this at the tenth minute of each hour, every day of every month”. So our monitoring script won’t execute every 10 minutes, but only at midnight 10, 1:10, 2:10, 3:10, 4:10 and so on.

So how are we supposed to say “every 10 minutes”, then? Well, we can simply “divide” the minute star by 10.*/10 * * * * bash /root/monitoring.shIf the wall command wasn’t incorporated directly into the monitoring.sh script, we can pipe it into this cron rule, like so:

*/10 * * * * bash /root/monitoring.sh | wall

-

WordPress Setup

- What is WordPress:

WordPress is a free and open-source content management system (CMS) primarily used for creating websites, blogs, and online stores. It's one of the most popular website-building platforms globally, powering millions of websites on the internet.

WordPress provides a user-friendly interface, allowing individuals and businesses to create and manage their websites without needing advanced knowledge in a scripting language. It offers a wide range of themes and plugins, which extend its functionality and customization options.

To setup a WordPress website we need three essential requiSITES, 'see what i did there, nevermind back to the subject!', a scripting language (PHP), a webserver manager (Lighttpd) and a database manager (MariaDB):

PHP:Or Hypertext Preprocessor, is a very popular open-source programming language for the creation of dynamic web pages via web server. It is essential for the correct operation of WordPress.

Lighttpd:Or Lighty, is an open-source web server software designed for speed, efficiency, and scalability. Its primary job is to serve web content to clients, such as web browsers, efficiently and reliably. It can handle incoming HTTP requests from clients and delivering the appropriate web content in response.

MariaDB:MariaDB is a popular open-source relational database management system that is widely used for storing and managing data in various applications and websites. Its primary job is to provide a reliable, scalable, and efficient platform for storing, organizing, and retrieving structured data. MariaDB stores data in a structured format within tables, which consist of rows and columns. It supports various data types such as integers, strings, dates, and more.- WordPress Installation:

To install PHP one packet is not enough, we need some dependencies,php-common,php-cgi,php-cliandphp-mysql. However if you want to install latest vervion of PHP you can check this.

$ sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade $ sudo apt install php $ sudo apt install php-common php-cgi php-cli php-mysqlTo check PHP’s version on the Born2beroot system, let’s do this command:

$ php -vThe open source web server that we have to choose here is lighttpd (or “lighty“). With a smaller memory footprint than other web servers (like Apache). However, it is very possible that Apache was installed on our server as a dependency for one of the PHP modules. To avoid conflicts between our web server lighttpd and Apache, the first thing we will do is check if Apache was installed and, if that is the case, uninstall it:

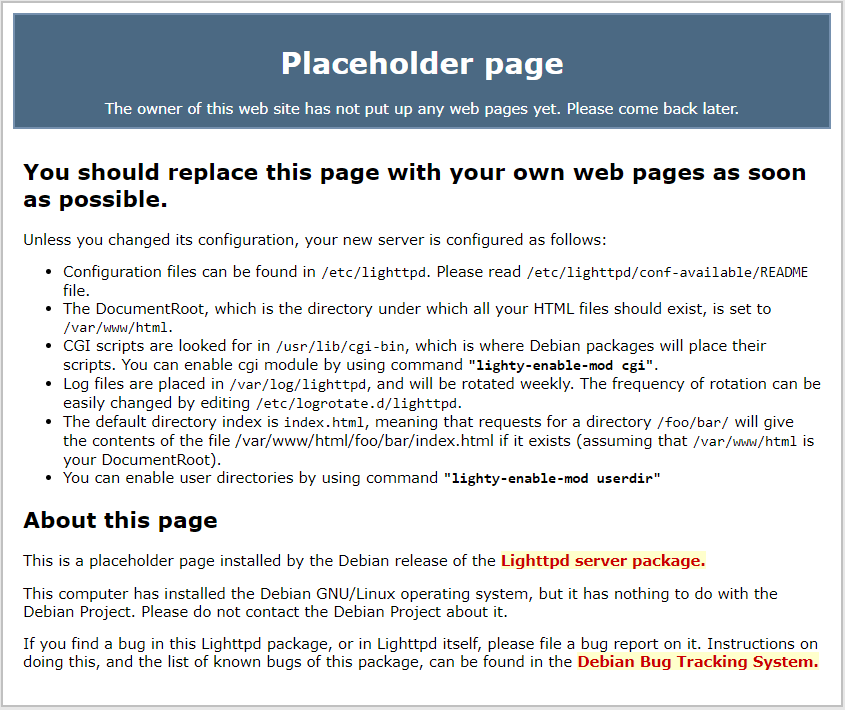

$ sudo apt list apache2 $ sudo apt purge apache2 $ sudo apt install lighttpd $ lighttpd -vThen we will start it, enable it at system startup, and check its version and status with the following commands:

$ sudo systemctl start lighttpd $ sudo systemctl enable lighttpd $ sudo systemctl status lighttpdIts status should show active. All that is left to do is authorize HTTP traffic in our firewall settings:

$ sudo ufw allow httpwe should see that port 80 is allowed. Port 80 is the default HTTP port. We also need to do some port forwarding in VirtualBox to be able to access to the virtual machine’s port 80 from the outside, like we did before for port 4242:

- What is WordPress:

Settings >> Network >> Adapter 1 >> Advanced >> Port Forwarding Add a rule for Host Port: 80, Guest port: 80.

Finally, we can do a little test to check that lighttpd is working properly. In a browser on the host machine, we can connect to the following address and port: http://127.0.0.1 (or http://localhost). We should see the lighttpd placeholder page, like this:

Let’s do another quick test. In the virtual machine, let’s create a file named info.php in the /var/www/html directory like so:

$ sudo nano /var/www/html/info.php

Here we will write a small script to show information about PHP on this server:

<?php

phpinfo();

?>Now in our host browser, let’s go see this file at the following address: http://127.0.0.1/info.php.\ …And we get a “403 Forbidden” error… What is happening here?

-

Activating FastCGI

FastCGI (Fast Common Gateway Interface) is a protocol used for communication between web servers and dynamic content generation engines like PHP, Python, Ruby, and others. Its primary job is to improve the performance and scalability of web servers by reducing the overhead associated with handling dynamic content.FastCGI allows web servers to delegate the execution of dynamic content generation scripts to external processes called FastCGI applications. These applications can be written in various programming languages and are responsible for generating dynamic content in response to HTTP requests.

So let’s activate lighttpd’s FastCGI modules with the following commands:

```

$ sudo lighty-enable-mod fastcgi

$ sudo lighty-enable-mod fastcgi-php

$ sudo service lighttpd force-reload

```

Now, we should see a page like this when we go to http://127.0.0.1/info.php:

- Installing MariaDB

WordPress stores the contents of a website in a database. MariaDB is a free, open source database manager, based on MySQL. To install it, we only need to do:

$ sudo apt install mariadb-server

Then, we will start, enable and check the status of MariaDB:

$ sudo systemctl start mariadb

$ sudo systemctl enable mariadb

$ systemctl status mariadb

We should see that MariaDB is active. But we still need to secure its installation with the command:

$ sudo mysql_secure_installation

To set up MariaDB’s security parameters, we have to answer several questions (and here, root doesn’t refer to our virtual machine’s root user, it refers to MariaDB’s root user!):

Enter current password for root (enter for none): <Enter>

Switch to unix_socket authentication [Y/n]: Y

Set root password? [Y/n]: Y

New password: 101Asterix!

Re-enter new password: 101Asterix!

Remove anonymous users? [Y/n]: Y

Disallow root login remotely? [Y/n]: Y

Remove test database and access to it? [Y/n]: Y

Reload privilege tables now? [Y/n]: Y

We must then restart the MariaDB service:

$ sudo systemctl restart mariadb

Now that MariaDB is properly installed, we need to set up a new database for our WordPress website.

$ mysql -u root -p

We will need to supply the root password for MariaDB (not the VM’s root password!). Finally, we can create our WordPress database with the following SQL commands:

MariaDB [(none)]> CREATE DATABASE wordpress_db;

MariaDB [(none)]> CREATE USER 'admin'@'localhost' IDENTIFIED BY 'WPpassw0rd';

MariaDB [(none)]> GRANT ALL ON wordpress_db.* TO 'admin'@'localhost' IDENTIFIED BY 'WPpassw0rd' WITH GRANT OPTION;

MariaDB [(none)]> FLUSH PRIVILEGES;

MariaDB [(none)]> EXIT;Now if we go back to MariaDB with the earlier command mysql -u root -p and we do:

MariaDB [(none)]> show databases;We should see something like this:

+--------------------+

| Database |

+--------------------+

| information_schema |

| mysql |

| performance_schema |

| wordpress_db |

+--------------------+

Our wordpress_db database is there.

Before we can start installing WordPress on our Born2beroot virtual server, we need the following packets: wget to download from a web server, and tar to decompress a file.

$ sudo apt install wget

$ sudo apt install tar

Then, we will download the archive of the latest version of WordPress from the official website, extract it and place its contents in the /var/www/html directory (if you want to be fancy you can place the files at /srv). Then we will clean up the archive and the extraction directory:

$ wget http://wordpress.org/latest.tar.gz

$ tar -xzvf latest.tar.gz

$ sudo mv wordpress/* /var/www/html/

$ rm -rf latest.tar.gz wordpress/

We need a configuration file for WordPress. A sample is included in our files, so let’s rename and edit it:

$ sudo mv /var/www/html/wp-config-sample.php /var/www/html/wp-config.php

$ sudo nano /var/www/html/wordpress/wp-config.php

Here, we want to modify the database parameters to direct WordPress toward the one we created with MariaDB.

<?php

/* ... */

/** The name of the database for WordPress */

define( 'DB_NAME', 'wordpress_db' );

/** Database username */

define( 'DB_USER', 'admin' );

/** Database password */

define( 'DB_PASSWORD', 'WPpassw0rd' );

/** Database host */

define( 'DB_HOST', 'localhost' );Lastly, we need to change the permissions for the WordPress directories for the www-data user (our web server) and restart lighttpd:

$ sudo chown -R www-data:www-data /var/www/html/

$ sudo chmod -R 755 /var/www/html/

$ sudo systemctl restart lighttpd

Finally, we can connect to http://127.0.0.1 in our host browser to reach the WordPress installation menu for our new website.

There! Once the installation is complete, we can connect and customize our website however we want. Anything is possible!

-

Fail2ban Setup

Fail2ban is a program that analyses server logs to identify and ban suspicious IP addresses. If it finds multiple failed login attempts or automated attacks from an IP address, it can block it with the firewall, either temporarily or permanently.

This is the service we will install for the second Born2beroot bonus. We will then start and enable Fail2ban, as well as check its status.

$ sudo apt install fail2ban

$ systemctl start fail2ban

$ systemctl enable fail2ban

To configure Fail2ban we need to head to /etc/fail2ban/ and make a copy of jail.conf and fail2ban.conf and name the new copies : jail.local fail2ban.local

$ sudo cp /etc/fail2ban/jail.conf /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

$ sudo cp /etc/fail2ban/fail2ban.conf /etc/fail2ban/fail2ban.local

$ sudo nano /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

To apply Fail2ban to SSH connections, we have to add a few lines to the file jail.local under the “SSH servers” section that starts at line [274]:

...

#

# SSH servers

#

[sshd]

# To use more aggressive sshd modes set filter parameter "mode" in jail.local:

# normal (default), ddos, extra or aggressive (combines all).

# See "tests/files/logs/sshd" or "filter.d/sshd.conf" for usage example and details.

# mode = normal

enabled = true

maxretry = 3

findtime = 10m

bantime = 1d

port = 4242

logpath = %(sshd_log)s

backend = systemd

...We can do the same for Lighttpd:

...

[lighttpd-auth]

# Same as above for Apache's mod_auth

# It catchis wrong authentifications

enabled = true

port = http

maxretry = 5

findtime = 10m

bantime = 1d

logpath = %(lighttpd_error_log)s

...When we're done configuring we should restart Fail2ban service:

$ sudo systemctl restart fail2ban

In order to see the failed connection attempts and banned IP addresses, all we need to do is use the following commands:

$ sudo fail2ban-client status

$ sudo fail2ban-client status sshd

$ sudo tail -f /var/log/fail2ban.log

To test that Fail2ban is actually banning IP addresses, we can change the SSH ban time to a lower value, like 30m, in the /etc/fail2ban/jail.local configuration file. Then try connecting multiple times from the host machine via SSH with the wrong password. After a few attempts, it should refuse the connection and the fail2ban-client status sshd command should show the banned IP address.

And that’s it for the Born2beroot bonuses!

Debian Installation & Configuration.

SSH.

ChatGPT & Phind.