- Background and Motivation

- Checkers Engine Implementation

- Evolution Implementation

- Static Evaluation

- Results and Reflection

- Trying it out yourself

An engine is a computer program that plays a certain game, such as chess, shogi, go, or checkers. In many strategy games, engines far outperform their human opponents (see Deep Blue vs. Garry Kasparov, AlphaGo vs. Lee Sedol). Unlike humans, who play through intuition and experience, engines typically find strong moves through brute-force computation and analysis of hundreds of millions of future positions.

Generally, engines are built from three major components, each of which can be approached in different ways:

- A move generator, which for a given board position generates a list of legal moves that can be played,

- A tree searcher, which - using the move generator - looks at a tree of possible future positions stemming from various candidate legal moves, typically searching several moves deep into the future, and

- A static evaluator, which without searching any deeper attempts to gauge how promising a particular position is for a certain player. When the tree searcher reaches its desired search depth, it calls the static evaluator on the position at the end of the variation to obtain a final "score" that can be used to decide whether it is worth it or not to proceed down that variation.

Move generation in most top-level engines are done with bitboards, which are extremely small and simple data structures usually consisting of a few primitives, such as unsigned 32-bit integers or 64-bit longs. Today's x86-64 CPUs are highly optimized to perform bitwise operations on these primitive types, and thus by manipulating bits in a clever way move generation becomes extremely fast (and memory usage is also low). However, move generation can be approached in other ways; notably, Sunfish (which, although weak in comparison to other engines, is still quite strong compared to humans, with a 2139 Elo on Lichess.org) uses a list of characters to hold the board state and lazily generates moves using Python's yield keyword. neche uses bitboards to generate moves.

Tree search can be done via the famous Minimax algorithm, which simulates games along different variations, checking all legal moves in the position, and logically deduces the best next move assuming best play from the opponent. For games with a high branching factor, such as Go, minimax is not as viable, as the number of positions to check grows exponentially with the branching factor. Thus new options for tree search have been developed, such as Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS), which is the searching algorithm employed by AlphaGo. For checkers, the branching factor is very low (2.8, compared to Go's 250) and thus minimax is a better option. neche uses minimax to probe future positions.

In move generation and tree search, neche adopts traditional approaches for engine implementation. However, it differs in its approach to static evaluation of positions.

Classically, static evaluators are programmed to look at a set number of heuristics, or features, about a given position. These heuristics often come from centuries of human experience and are manually tuned to achieve the desired result. For example, Chinook (a strong checkers engine) looks at around twenty different heuristics, including material count (whether or not it has more pieces than the opponent), how far advanced its men are (closer to promotion), and how centralized its kings are (kings that are closer to the center of the board control more squares and can better dominate the opponent's pieces). Stockfish, prior to the addition of NNUE, looked at piece mobility, king safety, pins, and outposts in its static evaluation function of chess positions. These heuristics are all very human descriptors of positions, and though accepted to be generally good rules to abide by, are not necessarily the whole truth.

The development of AlphaZero showed that this is not the only way to create a strong engine. AlphaZero was unique in that it was developed with zero knowledge about what is considered by humans to be a "good move", and rather fine-tuned its static evaluator through reinforcement learning, playing millions of games against itself. Rather than using manually-tuned parameters, AlphaZero was a neural network with a set structure, which trained itself through backpropagation.

neche is an attempt at yet another approach to creating static evaluators for engines. Like AlphaZero, it requires zero human knowledge; initially, neche has no idea that more pieces is good, or that men should be pushed down the board so they can become kings. However, unlike AlphaZero, it is not a large, complex neural network with a defined architecture. Rather, it is a "population" of tiny "brains" (from here on I will prefer using the terminology "networks" or "neural networks"), each with only a few neurons, that continuously evolves to become stronger over time.

Before we get to the static evaluator, however, we must first build the move generator and tree search. These are not unique to neche, and I use very standard, mainstream concepts and algorithms to achieve this functionality.

Although many board representations are possible, bitboards are well-known to be extremely fast and optimized for move generation as they boil down directly to simple CPU instructions such as SHL/SHR, ROL/ROR, LZCNT, BSF, AND, RBIT, etc. that can be executed at lightning speed. Note that on a checkers board, there are 32 squares that pieces can go to (8x8 grid, but half the squares are not accessible). This works out perfectly, as an entire board can be stored in just three 32-bit unsigned integers, one encoding the locations of all of the white pieces, one encoding the location of black pieces, and one encoding the location of kings.

I use a bitboard layout that I designed myself (as far as I know, this is a novel layout for checkers, as I can't find this online), shown below:

| 31 | 23 | 15 | 7 | ||||

| 30 | 22 | 14 | 6 | ||||

| 21 | 13 | 5 | 29 | ||||

| 20 | 12 | 4 | 28 | ||||

| 11 | 3 | 27 | 19 | ||||

| 10 | 2 | 26 | 18 | ||||

| 1 | 25 | 17 | 9 | ||||

| 0 | 24 | 16 | 8 |

Here each number on a square corresponds to the index of the bit in the 32-bit integer that holds whether or not there is a piece on that square. In other words, if this was the integer holding the white piece locations and we wanted to encode that there are no white pieces on the board except one on the very top-right square (square number 7), our corresponding integer would be all zeros except the 7th bit (from right), i.e. 0b00000000000000000000000001000000 = 64 in base 10.

Note that this layout yields many useful properties for checkers:

- A move to the up-right is equivalent to a leftward rotate by one bit;

- A move to the up-left is equivalent to a leftward rotate by nine bits;

- A move to the bottom-right is equivalent to a rightward rotate of nine bits;

- A move to the bottom-left is equivalent to a rightward rotate of one bit;

- "Flipping the board", i.e. rotating by 180 degrees, is simply reversing the order of the bits and applying a leftward rotate by 8 bits.

Let's see an example of bitboards in action. Suppose for the below position:

we want to find all legal moves in which a white man (not a king) slides upwards and to the right.

Our bitboard representation of the position looks like this:

- white pieces:

0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 - black pieces:

1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 - kings:

0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

One way to approach the problem is to try to first find all open squares that a man could move to. Since we are looking for up-right moves only, we know that all of the squares on the left column and bottom row are inaccessible, because there is no way a piece could get to those squares by moving to the top-right. We'll mask off those squares. Additionally, squares that are currently occupied by a piece (doesn't matter the color) cannot be moved to because they are already taken. We can thus compute this intermediate bitboard of open squares (notice that the 1s in this bitboard correspond to open squares in the position that aren't on the left column or bottom row):

open_squares = MASK & !(white | black)0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0

Since we only care about men, let's also get rid of the 1s in the white bitboard that are kings:

white_men = white & !kings0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0

Recall that a useful property of the bitboard layout is that we can easily express movement as bitwise shifts and rotates. So what if we shift the open_squares bitboard back onto the white_men bitboard? In other words, to find all men that have an available square to the up-right, we can just shift open squares to the bottom-left (according to the bitboard, thats a rightward shift by 1) and perform a bitwise and, like so:

white_movers = (open_squares >> 1) & white_men0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

And we are done. Notice this bitboard now has 1s corresponding to every man on the original board that has an up-right slide available. All that is left is to get each set bit out of this bitboard, one at a time, which can be cheaply achieved by CPU instructions such as CLZ, TZCNT, or BSF.

Similar bit-twiddles can be employed to generate king slides, promotions, and captures. Because in checkers we have "double jumps" and chains of captures that may branch out in different ways, to generate all possible captures I employ a simple depth-first search that pushes intermediate captures onto a stack of moves for further exploration, until all captures are exhausted. For more information on how these moves are generated, refer to the source code, namely bitboard.rs.

For tree search, neche implements a rather primitive, textbook single-threaded minimax algorithm with speedups through alpha-beta pruning and memoization in the form of a transposition table stored as a hash map.

Minimax without optimizations is similar to a depth-first traversal, in which each node is a position, and each outgoing edge connecting to child nodes is a legal move generated by the move generator. This can be quite costly to compute; checkers has a branching factor of about 2.8, which means on average each node will have 2.8 children. Searching at a depth of 10, this equates to about 30,000 positions to evaluate.

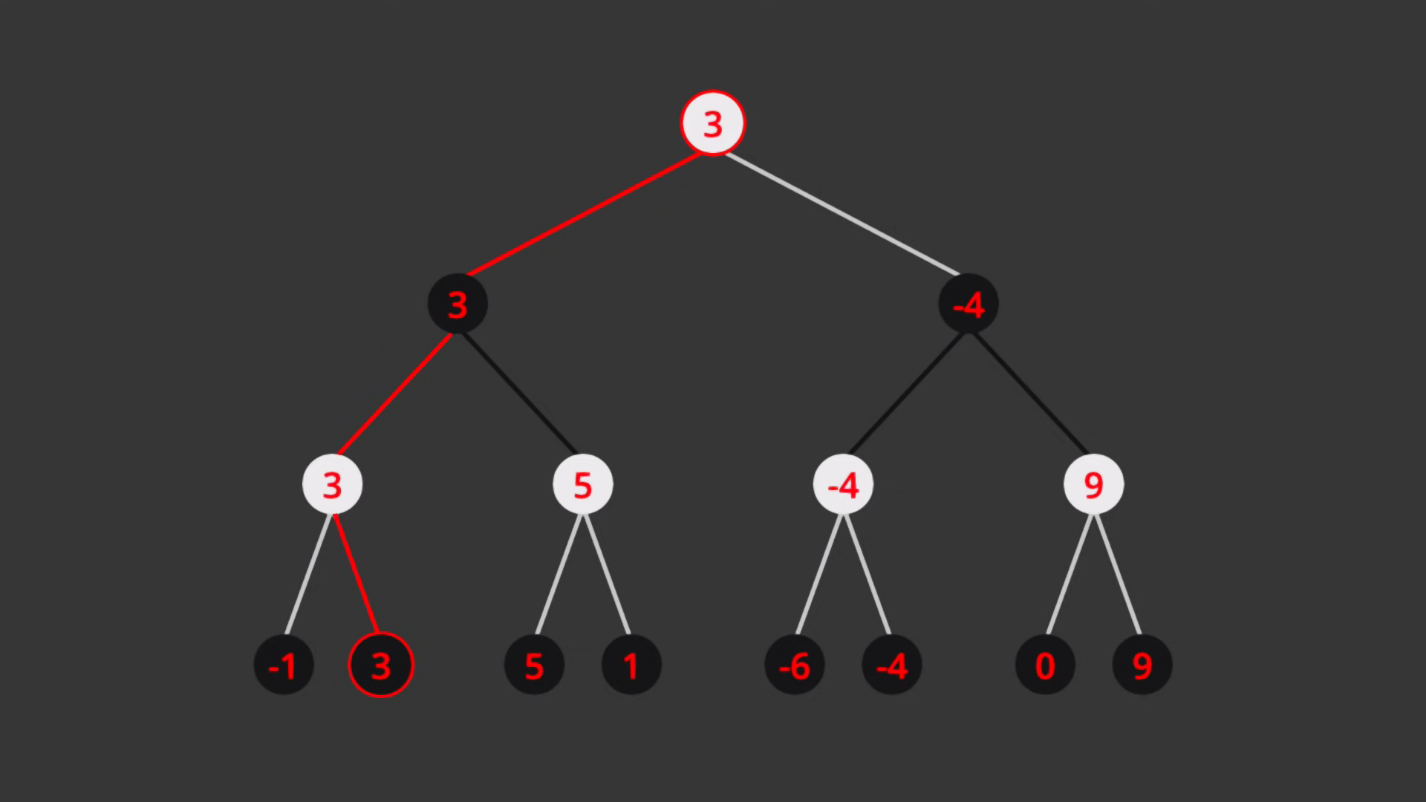

(Photo credit to Sebastian Lague, YouTube)

Once we search to the desired depth (in the above image, depth = 3), we stop generating child moves and perform a static evaluation on the positions (here, the black row of nodes at the bottom of the tree). Then, white, the "maximizing" player, will always play the move that maximizes this evaluation, while black, the "minimizing" player, will always play the move that minimizes the evaluation. In the above case, notice that each white node in the second row of nodes from bottom takes on the greatest evaluation of its two child nodes, as white will play the move that leads to that greatest evaluation. Likewise, the two black nodes above that row take on the minimum value of their children, as black will always play the move that leads to the minimum evaluation.

Instead of naively searching and evaluating every possible position, neche has two ways to induce an early cutoff and "prune off" large branches of the search tree:

- alpha-beta pruning. When we know for sure that our opponent would never proceed down a certain variation because they have better options available, there is no point in searching it further.

- transposition table. Playing two moves in different order would land us in different parts of the tree, but with the same position on the board. It is unnecessary to put in redundant effort to reevaluate this identical position, so instead we keep track of positions we've seen before. This process is known as memoization.

Another optimization is that moves are generated in a specific order in an attempt to induce an early cutoff; for example, captures and promotions are usually beneficial, so they are generated in an order where they will be searched first to try to cause more alpha-beta pruning to occur later on. Sliding king moves are often not that productive, so they are searched last (and probably pruned off before we search them). Unfortunately, because neche networks are pretty dumb, the move order generation is not necessarily as helpful; however, it is important to note that this optimization does not "pollute" neche network's evaluations of positions with human knowledge. In other words, this optimization can only help networks search faster in certain cases, but does not have any effect on the networks' final evaluations of positions.

Another issue with naive minimax is that it may be the case that the position at the end of the variation has imminent action possible. This would yield inaccurate evaluations of the position, as for example the static evaluator may think it has a good position because it has a material advantage, but is unable to see that a large number of its pieces are about to be captured on the very next move.

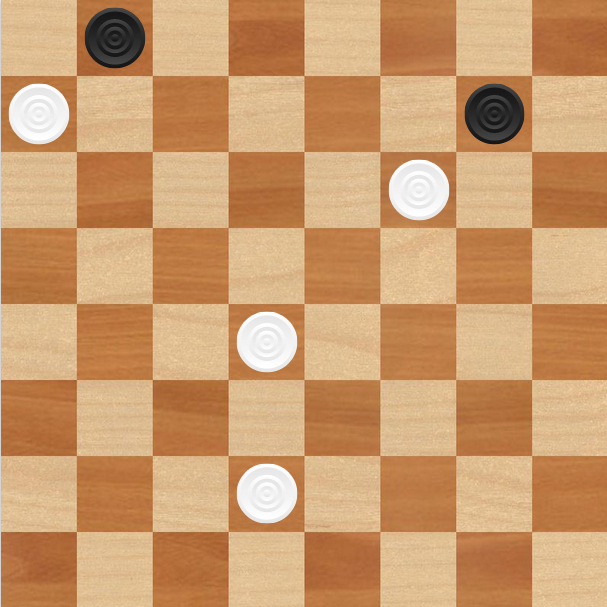

Above is a position where the engine is playing white and is evaluating the position statically with black to play on the next move. With naive minimax, the engine may mistakenly believe that white has a significant advantage due to its material advantage and far-advanced pieces; however, in reality white will lose on the next move after black does a triple-jump with promotion to a king.

To combat this problem, neche also does a quiescence search at the end of each line to only evaluate "quiet" positions, or a position that we know to be stable and without captures possible. The q-search proceeds after the desired search depth has been reached by the naive minimax algorithm, and searches with infinite depth on only capture moves.

After concluding minimax + quiescence search on all available legal moves, neche networks randomly select a move out of all of the next moves with equal evaluation. This ensures that the "order of move generation" optimization has no effect on the final move choice, and removes the influence of bitboard move generations on the predictability of moves.

For more details about how searching works, please refer to the source code, namely search.rs.

Before discussing the static evaluation component of neche, we must first turn to how evolution is implemented.

Recall how I described neche as a "population of tiny networks" that evolves over time. This process of evolution is modeled closely after evolution in the natural world.

Like living organisms, each individual in the population of networks has its own genome, which is a string of DNA base pairs. In neche, I have arbitrarily set the genome of each individual to consist of 200 separate genes, each 16 base pairs in length. Here is an example of what a genome looks like:

CAGTAGGACGGGTGAGTTAATGAACTTAGCCTCCGCGGTACAAAGGACGACACCGCCGGCACTGAGGAGTCGTGCACTAACATTAAAACCCCCTGACTACACCATTGACGCGAGGCATAAAGGCAACAATCAATAAAAGAGCACTGAGCCCTGTGTTGACGAACATGGGCTGACCGCGGCTATTTCGAGGGAACTCTAAGGAGACAAGTCGGATCTAGACGCGCGCATCTGACGATTTGCAAAATGCCCGCGCACACTTCCAGACGTTAGAAAACCAACGGCCGCATCCGCTAAAATCGTTTAAATTTATGCAACAGCTTCTGCCTCTTGCCTGTCGATTGTTGTATGGTTAGGATCAGGGTCGCCCGAACCAACGTTACAACCCAGCGCTGCGATGCTTAGGGAATGATTCCGGATTTGGGGGCTATAGTGGAGCGGGATATGTCCGATAACTCTCGGCTACTGAACTCAGACTCATGTCGTGAAGTAATAACTGCCGGTGCTCGTGACATGGTAAACCAGACGTTTCTCAAGGAGACTATTCACGACAATCCCAAGTCTAGCAGTCCTTCCTTTAAACCTGCGTTCTAGGGGTGAGTTCGAAAGAAACAGCAATGAGGACTCGACACGACCGACTGATTATGACGGGCTATAATCTCACTTCACATTCCTCGTGAGAATTAGATAAGGCGGTAGATCGAACCCCTCTTGTGAGAGATGTCAGGGCGACACTATTTATTGACAGGATAGCATTCATTGGATAAAAGTTTCGAACCTAGAGCGTAGGATTTTAACGGAGGGGTTTGCGAATACAACCTCCTGGAACGCCGAACCCTTCCCGAAGGCTGAAACTTACGTACCGCTTACCAGTCTGTGTTGGGTCGCCAAATACTAACCCGGATTAAAAATGCCGGCCGCGCCTTACTCCATGACTACGGGAGAATCGACAATGCCACTTGTCTACGAATCCACGGGACCAGTCAGGGCTGCCCACTATACTCGCTACATCCAGGTTCCACTCCCGACGGGGACTAAATGGATATGTAACCTTAACCCAAATATCGCGATTCTTTAGGCAGCCACGTAGTTCCGAAGAGCTGATCATGGTAAGCTCTTTTTAATTGCCCGATTCAATGGACCGAGTCGCGTTGCGCGTGAGGTAGGTGATGCCTTGAGGGTGAAGAGATTGCTGATATAGGGTTCGGGGGTATCCACGGAGAGGGGATTGGCCCGAAAGGCCAGCAGTTCGGAGAATTGCGAAAACTAGCGTATGGGCGATATCCTCCAAACTAACAAGCGGTCTCGCTCGGCGGAGGCGCGGAAGGAGCTCTCCACAATTAGAGCGTCCACAGACGCGCTTGTCAAGTCGATGTTAATAGTAGAAGTCTCGCTAGTGCAGGTATGGCACCGGCTGTGCGCATACATTTAGGTCACCTTCACTCAGATACTGATCTAGGGTCCGGCTTGTTGTTCCTACCGATCATGACAAGTGGATGGCAGACGTTAGACGCGAACATCAAAATCTTTAATTCGGCGCGGGCACCTAGCAGAACAGCCGGTAGGCATAACGCTGTGAGCCCGAAACGGACTTACGACTCCACGAGCAGAGGATCTCTTTGTTTTTAATCCATTCCAAATTTGGAACGTATCCTTGGCGAGGACAGATCTCCCTGGGAGCGTAGTCAAAAACTCTTAATTTGTTTGACAGACTCTGCTACCGCACTGTCGCATTAAGTCTTACTTTCCATCGGATCGCGACCGCTCAAAGTCTCGTTCCGGACCGCTGCGCAGGCCAGGCAGATGAGCCAGGAAGAAACCTTTTCGCACCGCAGGCGCTGTCCAGCGAAACATAATACTGTGTAGTGGCACGCTGCATCGCTTTACAATAACAGGCCCCCCATATCGCAATAACAAGCTTCCGGTGTAGCCAGAGCCCTGTGTTTCGTCCTTAGAGGGTATGATGGCTTCCGAGTCCGCCATTGCAGACGGATAGCTCAACCAGTTAGGCCGTTTGTGAGAACGACCAGGAGAGCCAATAGTTTTTGCCAGGCCTTCCCCGCTACTTGAGCGTGTTTCTCAGTTTCAGGGCTAGATGGACTACCGCCGGGGTCTCTCCCATAGGTTAGTAGGTATGTGGCCATGCAGTTACGATTTAGAAACAATAGCCGTAATTCTAGCTACTTATGCCAACGTGGAATGGTATATGGAAAGCATGAGGCCTCTGAAAATAACCAACAGCCAATCGAGCGCGCTTGCTCCATATTCGGCCAAGCCCATATTCCGACGGATTATTATCGGTTACCTATGGTAACCCACAGCCGAGCGGTACTGCATTATTTAGTACAAATGAGTAGTTGTATCTACGCCGACGTGGTACATCCTTGGGTCTATTCTAATCAGCCAATCAGCGGTTCCATAAGTTGACGCGGTATAGTAGCACTTCTGTAATAACCTTTCATAGGTTAGCACGCTAGGAAACCGCGAGGGTACGACAGAATTAGATACTATGGAGTCTACGAGGCAGATTGACGATGACAGTGCACGCTATCTCCGGGGGACGCTTGTCCTCTTGCGCTGCAGCCTAGTTGTCCTGCTGGCGACGCGTATTACTGATATGGGTAGGTACCCCTAGCCGGCGCTTTACGCACATATGCATGGACTAATCGAACCAGTACCAAATTTAGGCCACCCCGAGATTACGGCAGCAACATGGAATGCAAGTAGGCCTGTCCAGCCATTACACACTTTATAGACCGGTGTAAATCAACCCTACGATGAAACACAACGTAAACAACGTCCCATTGGGTCGTGCGGAGCTAGAACTATGGACTATTCTACCGTCGCGGTCGTTTGATTATACTTGCCCTTGTTTACCAAACGTTGTGCCGGTAGAATGTTCGATATGACTACATTTCCGCACATCAGCGTCCCTGCTGCGCCCGATTAGAGATTATTAATGCTGTGGCTGGAGCTCATGTCCTTCTGGGCCCACGGGCGCCCTTCTGGAAGCCGTCCGGGGTGTAGCGACAAATGGTCAGGACACAGGTCCTCTCGTGCAAAAATCTGTCCACGAGTACAGCTCTACGGCGGTCGCAGTTCTGAATGACTCTATATCCTCAGTTATTACTACCGCAGGGTATATTCTATCGCACCTTCTCTCCCTTTCCCGCGCTCGGTAACAATCAAGTTAGTATACAACT

Notice how it looks very similar to a segment of DNA; it even shares the four nucleotides A, T, C, and G that are present in human DNA.

Unlike human DNA, however, nucleotides are not interpreted in codon triplets; instead, here the four base pairs encode numbers in the base-4 numbering system, as shown below:

| nucleotide | base 2 | base 10 |

|---|---|---|

| A | 0b00 | 0 |

| C | 0b01 | 1 |

| G | 0b10 | 2 |

| T | 0b11 | 3 |

As mentioned earlier, each "gene" in the genome is a string of 16 base pairs. Each gene encodes a "synapse" between two neurons, or a connection associated with a certain weight. The first three base pairs of the gene encode the ID of the source neuron, the second three base pairs of the gene encode the ID of the sink neuron, and the final ten base pairs encode the weight in base-4.

Each network has 64 different neurons to work with, each associated with its own unique ID. Their purposes are listed below.

| Neuron ID | Purpose | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 31 | Sensory neuron | Looks at one specific square on the board, firing with different values based on if the square is occupied by a white king, white man, black man, or black king. |

| 32 - 38 | Bias neuron | Fires with a value of 1 unconditionally. |

| 39 - 54 | Layer 1 ReLU | Sums up its input values and performs the ReLU function on the sum to induce nonlinearity before passing it on through the network. |

| 55 - 62 | Layer 2 ReLU | Same as Layer 1 ReLU, except can only connect to output neuron. |

| 63 | Output neuron | Sums up input values and returns resulting sum as output of forward propagation. |

Because there are 64 different neurons, we can perfectly describe a specific neuron using any combination of three nucleotides (4 possibilities for each nucleotide, so 4^3 == 64). The raw weight is an unsigned integer which results from the conversion of the last 10 base pairs in the gene from base-4 to base-10. The raw weight is then converted into the realized weight by shifting the range of values to center around zero (by subtracting 2^19) and dividing by 10,000 to scale the possible values down to a reasonable range.

As an example, consider this gene:

CGATGGTAGTCGGATC

The first triplet of nucleotides, CGA, maps to the base-4 number 120, which in base-10 is 24. The neuron with index 24 is a sensory neuron, in particular the neuron that looks at the 24th square in our bitboard (C1). The second triplet of nucleotides is TGG, which maps to the base-4 number 322, which equals 58 in base-10. The neuron with ID 58 is one of the general-purpose layer 2 rectified linear unit neurons. Finally, the weight is encoded in the last ten nucleotides in the gene, TAGTCGGATC. This translates to a base-10 raw weight of 833165, which is converted to the actual weight as (833165 - 2^19) / 10000 == 30.8877. Thus this gene encodes a connection from the C1 sensory neuron to a layer 2 ReLU with a weight of 30.8877.

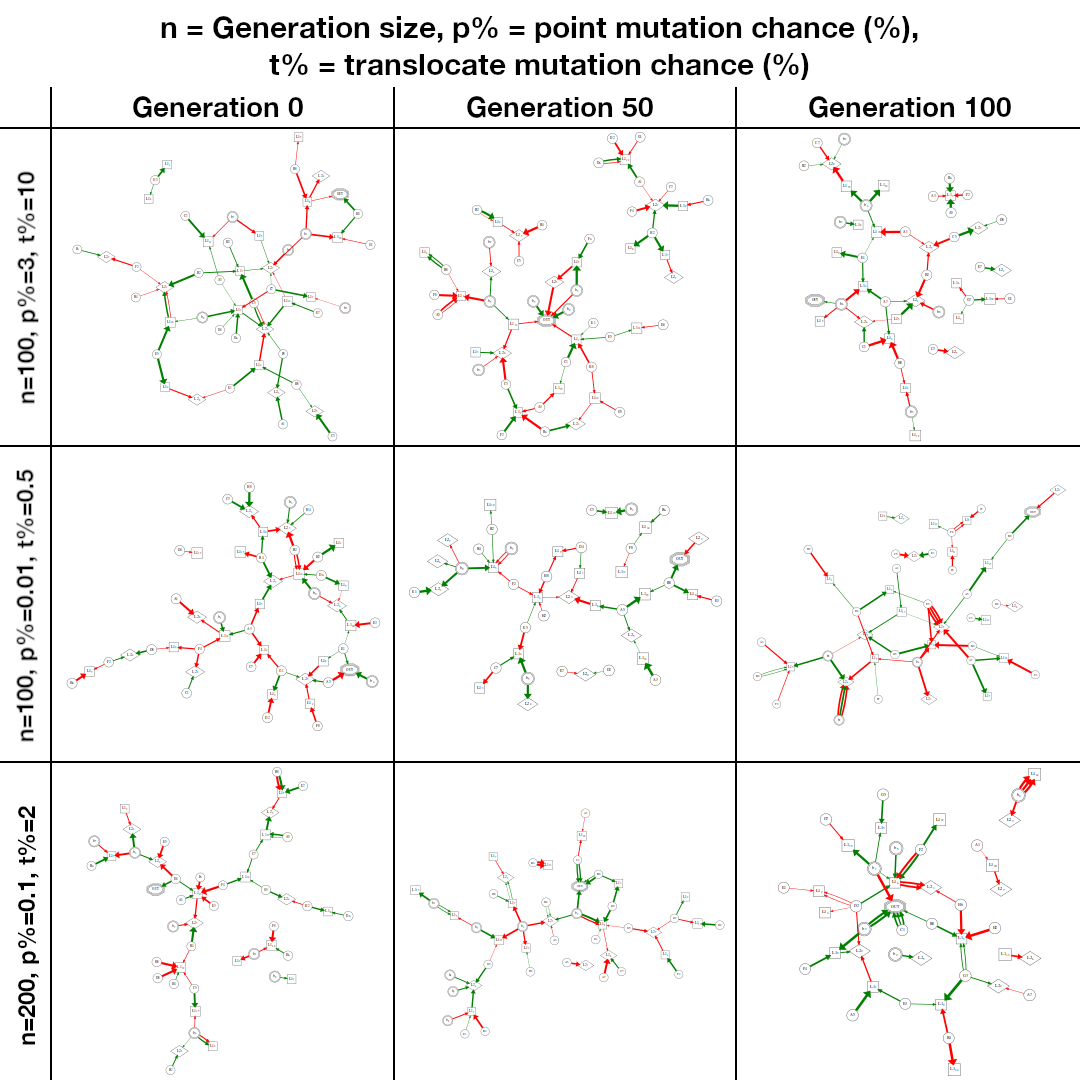

All of the 200 genes in the genome are structured in the same way. WIth 200 genes, we can represent up to 200 distinct synapses between the 64 neurons (it is often less, as invalid synapses that connect a neuron to itself or a neuron "backwards" through the network, i.e. connecting the output neuron to a Layer 1 ReLU, are considered inactivated genes and are ignored). Below are some examples of how a neche neural network looks.

You will notice that it does not have the same orderly, structured appearance as a classical feedforward neural network. This is because here rules are looser about what neuron can connect to what, so skip connections are frequent, and often parts of the network are not even linked up to the greater whole.

When neche first starts running, it has zero knowledge about checkers. All 200 individuals in the parental (F0) generation have completely randomly generated genomes that yield networks with no semblence of structure or clear plan, as can be seen in the example Generation 0 network above.

Individuals in each generation play games against each other to form a "ranking", or an ordering in which the strongest networks of the generation are given a higher score, and weaker networks are given a lower score. There are several ways I considered implementing this problem, all inspired from how tournaments are played in the real world:

- Round robin. Here every network would play every other network, and they would be awarded points based on if they win, drew, or lost. Their total score after playing against all other networks would be a indicator of their relative strength. This approach I ultimately decided against because it scales very poorly; for a generation with

nindividuals, we would haven(n-1)/2round robin games, giving us a complexity ofO(n^2)asymptotically. - Elimination tournament. Here networks would be organized into a bracket, and winners of each round would advance to the next round. This approach scales much better than round robin, as number of games will only increase log-linearly, but the problem is that order of elimination is not necessarily an indicator of network strength; in other words, we would be able to get the "best" network from each generation by doing this approach, but it is not necessarily true that the runner-up is the second strongest network; for example, it may be the case that the winner had defeated the second strongest network much earlier on in the rankings.

- Swiss-system tournament. Here players play against each other with similar scores, but avoid playing each other twice in the same round. The pairings in each round are determined by results of previous rounds. It enables us to overcome the challenges presented by round robin and elimination tournament, as after only a few rounds we will have a good idea of how to order the networks by strength, but it is very difficult and impractical to implement.

Ultimately, I chose to go with a "pseudo-Swiss style" tournament format, which draws inspiration from Quicksort. Here, each game serves as a "comparison" between two players, and Quicksort shows us that on average we only need nlog(n) such comparisons to sort all of the players into their appropriate ranks. Further speedups can be achieved by parallelizing this sorting process using pattern-defeating quicksort (pdqsort), which is already conveniently implemented through rayon::slice::ParallelSliceMut.

Because the networks behave in a non-deterministic manner (they randomly choose between equal evaluations), I chose to do 3 rounds of this pseudo-Swiss system per generation, and sum up each network's ranks from each round to obtain a total rank of its performance overall.

The final rankings of the networks from a given generation are offset and normalized to form a non-uniform distribution which we can randomly sample to determine parents for the next generation. The next generation still has 200 individuals; each individual's genome will be a mix of two parents, although there is no restriction that those two parents must be two distinct networks. Parents who had a more dominant performance in their generation have a higher probability in the non-uniform distribution to be chosen, and thus are more likely to pass their genes on to the next generation. On the other hand, weaker individuals will be far less likely to be a parent, and so their genes will be "weeded out" over time.

On my personal laptop, each generation takes about 20 minutes to run. While evolving, neche outputs debug information about the networks in each generation and the best network overall. This data can be used later on to see trends between generations and compare relative strength of networks from different generations. Additionally, this data can be used to "resume" evolution, picking back up where the program left off when it was terminated to avoid having to start from scratch again. For more information about the evolution process, see evolution.rs.

Much like in real life, two parental networks can create an offspring network by mixing their genes together. The process proceeds in two steps: crossover and mutation induction.

Crossover is a much simpler process here. First, both parent's genomes are split into genes and laid in parallel to each other (only three genes are shown below, but this happens for all 200 genes):

CACGCTATTGGGGACG CAACCCCATCCTTCGA ACCGGTCATACCGGTT

TAGACTAAGGTGGCCT GAATTGAGGATTTACG GGCATATAAGATGAGA

Then, from each "pair" of genes, one is randomly chosen to contribute to the child's genome:

CACGCTATTGGGGACG CAACCCCATCCTTCGA

GGCATATAAGATGAGA

Finally, the genes are "spliced" back together to form a continuous string of nucleotides, which concludes the crossover phase of offspring creation.

Then, we induce mutations into the child genome to maintain genetic diversity. neche does two different types of mutations: point mutations and translocation mutations. Point mutations are simply single-nucleotide substitutions that have a very small (<1%) chance of occurring. Below is an example of a genome before and after point mutations are induced:

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAACAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Translocation mutations are when one portion of the genome gets "broken off" and reattached at a different location. The reason why I included these was to allow genes to mix with "other areas", i.e. if there are two beneficial genes at the same locations in the genome it is possible for both to end up in an offspring if one is first translocated to another location in the genome in the parent and then crossover occurs. Below is an example of a genome before and after translocation. Notice how the repeat C and repeat G genes were excised and appended at the front of the genome.

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAACCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT

Translocation mutations occur at a slightly higher probability than point mutation reactions, because for each genome point reactions have 3200 chances of occurring (once for each nucleotide), whereas translocation mutations have only 1 chance.

After crossover and induction of point and translocation mutations, we are left with a finished child genome. A "viability check" is performed on the child genome, which simply ensures that there is at least one other neuron connected to the output neuron. If this is not the case, the brain is essentially vegetative, in that it is guaranteed not to respond to different board configurations. In this case, a new child is generated, until we have a child that has some value connected to output.

This process is repeated 200 times to produce the 200 children that populate the next generation of networks.

For more information about how genes and offspring generation are implemented, see genome.rs.

Each genome is dynamically parsed into a set of row vectors, through which static evaluation becomes nothing more than a forward propagation through the network; based on the board position, the sensory neurons fire with values in the range [-2, 2]; these values then flow through L1 and L2 ReLUs and then to the output neuron. The output neuron sums up all of its input values and returns a single value, which is interpreted as the network's eval score of the position. This value is then used in tandem with tree search and move generation discussed earlier to complete the checkers engine.

Because neche starts from completely randomly generated networks, it makes sense that the eval score of these F0 networks will be completely nonsensical. Most networks will just output 0 unconditionally; some will only look at a few squares, but with weights that make no sense. Gradually through evolution, improvements will be made in network structure as the genome becomes more fine-tuned.

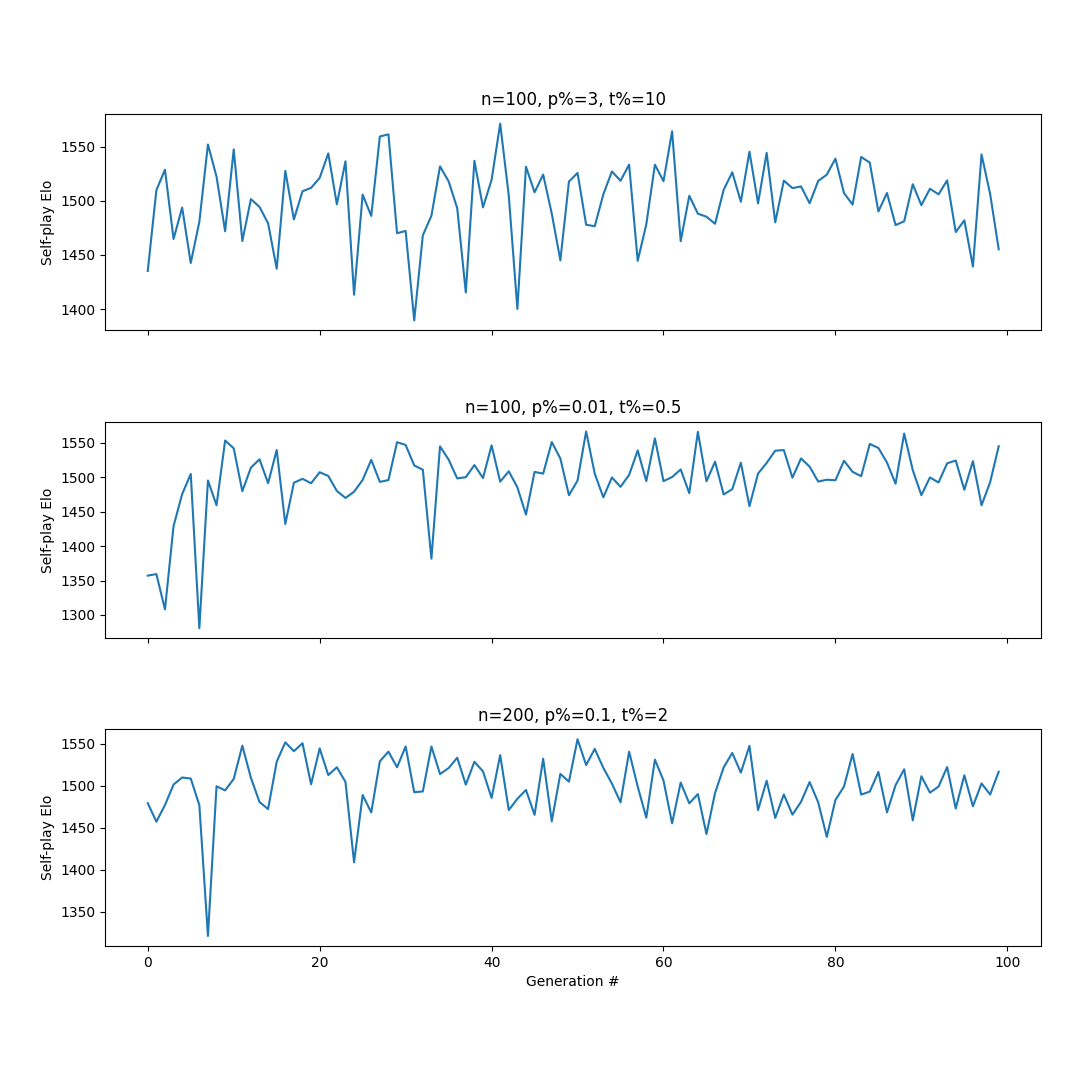

Ultimately, networks were not very successful at gaining strength over time, and seemed to quickly plateau after a small jump in performance in the early generations. A variety of different factors can be tuned, including mutation rates, search depth, generation size, and probability of stronger networks to be selected as parents.

Below are Self-play Elo ratings (no correspondence to actual human ratings) over generations for three different sets of factors. Let n be the population size per generation, p% be the chance of a point mutation, in percent, and t% be the chance of a translocation mutation, in percent.

It is interesting to see how the Elo graphs are influenced by mutation rates. Notice how variance of strength from generation to generation remains extremely high with higher mutation rates, and network strength is extremely unstable.

In the middle graph, mutation rates are extremely low, which results in much less spiking. However, by generation 150 genetic diversity had almost totally disappeared from the population, and the genome of each individual was virtually identical. This made the possibility of progress extremely unlikely for this setup.

The bottom graph attempted to correct for the loss in genetic diversity in the second attempt with both a large population size and medium mutation rates. I believe the increased instability in strength is due to the larger population size likely needing more generations to stabilize from random play; however, there still seems to be a plateau in strength centered around 1500 Elo.

Generally, I think neuroevolution is not a viable approach to evolving networks for checkers because random play turns out to be a fairly "decent" strategy. In checkers, typically all moves are "good" in some way; for example, captures are forced, so if there are captures available they must be taken, and captures are generally good moves. Additionally, if no capture is available then usually a man is pushed up the board, which is also a "decent" move as promoting men into kings is usually a good strategy.

It is also not necessarily true that a network that looks only at one square will play better than a network that doesn't look at any squares at all and blindly plays random moves. Thus, I believe this "plateau" of random play is extremely difficult to escape with these small population sizes and would require a miraculous series of mutations to make even a step of progress in the right direction.

I have no explanation for why there seems to be a large spike in strength in the first 5 or so generations, followed by a precipitous drop to all-time lows, in each of the trials.

Below are the strongest networks from the 0th, 50th, and 100th generations from those same three trials.

And here is a theoretical "strong network" that simply counts material on the board (this network was hand-designed by me and not made through evolution):

Stronger networks are possible, especially ones with finer-tuned weights and better-used inner neurons that take into account advancement of men, centralization of kings, and state of the game (opening, middlegame, endgame). Whether or not it is possible for evolution to produce these strong networks is unclear.

It is my personal belief that given a large enough generation size (probably in the thousands or tens of thousands), deeper search depth, and more fine-tuned mutation rates that help maintain genetic diversity between generations while also not being too extreme as to destroy any progress, such a theoretical network can eventually be produced. However, I have neither the time nor the resources to test this theory out, and my poor laptop fan has already endured enough abuse for the time being.

If you would like to try running neche yourself and seeing what kind of networks you get through simulating evolution, you will need an installation of Rust and decent hardware.

First, install rustup, which will also install cargo.

curl https://sh.rustup.rs -sSf | shThen, clone this repository to your local drive and cd into the created folder:

git clone https://github.com/brandon-gong/neche.git

cd necheFinally, install all dependencies, compile the project, and begin running the program by running:

cargo run --release

(Note the --release tag is critical; without it, neche runs extremely slowly)

neche will first search for the existence of a nechedbg folder; if it is your first time running the program, it will not exist, and so neche will begin evolution from scratch. Each generation, neche will write the genomes of all networks in the population to a file (n_nets.txt), and after the strongest network is determined it will add that individual's genome to best_networks.txt.

Evolution can be arbitrarily paused and resumed. When neche is run again, it will check for the existence of a nechedbg folder; finding its previous networks, it will pick up at the generation where it left off and continue evolving.

Currently, there is no simple CLI for manipulating generation size, mutation rates, and other parameters. Rather, you must manually change the source code and recompile to make those changes. I also have written write_to_dot and do_round_robin functions to help troubleshoot and inspect evolution's progress, however those must also be invoked manually in the main function. Perhaps at a later date I'll clean it up into a nice, clean executable, however today is not that day :)

If you would like to restart from scratch with new parameters, simply rename the old nechedbg folder to something else, i.e. nechedbg_attempt1. neche will then believe there is no nechedbg folder and restart from zero.