Implementation of a dynamic centered interval tree.

- Supports lookup for all intervals intersecting a query interval or point.

- Can be used with custom Interval classes.

- Lookups are in O(logn + k) worst-case time, where n is the amount of intervals stored in the tree and k is the amount of intervals returned by the lookup.

- Insertions and deletions are in average O(logn) time and O(n) worst-case time.

- Supports bounded and unbounded, as well as open and closed intervals.

Example use cases:

- Find all guests that had a booking at your hotel in a particular time period.

- Find all roads on a map, inside a given rectangular region.

- In a real estate site, find all customers that want to be notified per email, if a property in a specific price range has been submitted.

Why should you use a specialized data structure instead of just storing all intervals in an ArrayList and looping through it? Because it wil be very slow, if you are storing a lot of intervals.

The performance of the tree depends heavily on the ratio between reading and writing operations (RW ratio). Most real life applications tend to be read-heavy - it is expected to have much more lookups on the tree than insertions and deletions. The tree is going to perform exceptionally well in these situations, since the bottleneck in the list implementation are the lookups. In comparison, insertions in a list are incredibly cheep. But the tree performs very well in write-heavy applications, provided that the amount of stored intervals is sufficiently big. Let's check how the tree will perform in these mostly uncommon scenarios, where the application has more writes than reads.

| - | 5'000 inserts, 500 reads = RW ratio 1:10 |

50'000 inserts, 500 reads = RW ratio 1:100 |

500'000 inserts, 500 reads = RW ratio 1:1000 |

500'000 inserts, 500'000 reads = RW ratio 1:1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List insertion time | 2 ms | 2 ms | 12 ms | 10 ms |

| List lookup time | 56 ms | 777 ms | 13393 ms | approx. 9.5 days |

| Tree insertion time | 40 ms | 127 ms | 884 ms | 884 ms |

| Tree lookup time | 3 ms | 3 ms | 12 ms | approx 12 seconds |

| Total list time | 58 ms | 779 ms | 13405 ms | approx. 9.5 days |

| Total tree time | 43 ms | 130 ms | 896 ms | approx. 13 seconds |

| Efficiency = list time / tree time | 1.34 | 5.92 | 14.96 | approx. 63168 |

For the first benchmark we started with an empty list and an empty tree. Both data structures were then filled with the same intervals and the time needed for their insertion was measured. After that we ran lookup queries and recorded the total time needed for each data structure. Our experiment showed that it is worth using the tree even with a very uncommon write-to-read ratio of 90/10, as long as at least 5'000 intervals are stored in the tree. And the efficiency of the tree relative to the list becomes even bigger, if the size of the tree increases. In fact, for 1 Million insertions, it is enough to have as little as 50 queries to justify the use of an interval tree.

Another factor that influences the performance of the interval tree is the size of the output - the amount of intervals returned from a lookup. If a search query is expected to return the majority of intervals in the set, then the time complexity of a tree lookup will be close to linear, making the tree as efficient as an ArrayList. To measure how well the tree performs in these situations, we tried out different interval lengths. The bigger the interval length, the more intervals overlap, increasing the output size.

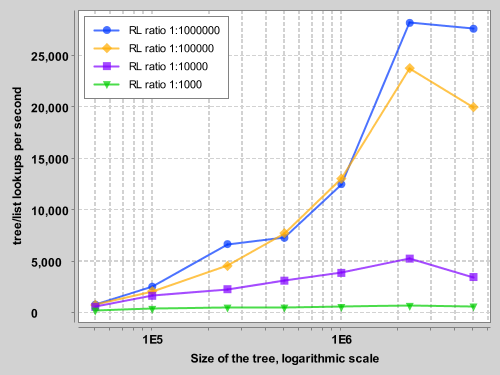

The graph shows a comparison of the tree performance with increasing interval length while keeping the range of the intervals constant (the possible values for the start points). We tried four different Range-to-Length ratios (RL ratios). The smaller the ratio, the bigger the expected output sizes are. As expected, lookups over shorter intervals have much better throughput and at tree sizes of a few million intervals lookups are 27000 times faster than with an ArrayList. With RL rato of 1:1000 the performance benefits start to drop significantly, but lookups are still over 500 times faster than list lookups, if the tree size is in the hundreds of thousands.

// Instantiate a new tree

IntervalTree<Integer> tree = new IntervalTree<>();

// Add some intervals

tree.add(new IntegerInterval(-8, 200, Bounded.CLOSED));

tree.add(new IntegerInterval(5, 120, Bounded.CLOSED));

tree.add(new IntegerInterval(-9, -1, Bounded.CLOSED));

tree.add(new IntegerInterval(15, 72, Bounded.CLOSED));

// Or maybe remove an interval

tree.remove(new IntegerInterval(15, 72, Bounded.CLOSED));

// Query for intervals intersecting [-4, 0]

Set<Interval<Integer>> result = tree.query(new IntegerInterval(-4, 0, Bounded.CLOSED));

// returns [-8, 200] and [-9, -1]The interval tree is built around a generic interval class. You can easily extend it and build your own classes to fit your needs. To get you started, the library provides implementations for the most common interval classes that you might need:

IntegerIntervalDoubleIntervalDateInterval

Both bounded and unbounded intervals are supported, meaning that you can have intervals extending from negative infinity and/or to positive infinity. The end points of the intervals can be inclusive and exclusive, so both open and closed intervals are supported.

There are several possible ways to initialize new intervals. You can use the provided Builder, for example like this:

new IntegerInterval().builder()

.greater(12)

.lessEqual(15)

.build(); // returns the interval (12; 15].

new IntegerInterval().builder()

.greaterEqual(-5)

.lessEqual(0)

.build(); // returns the interval [-5, 0].

new DoubleInterval().builder()

.less(0.2)

.build(); // returns (negative infinity, 0.2)

Date from = new GregorianCalendar(2014, Calendar.JULY, 6).getTime();

Date to = new Date();

new DateInterval().builder()

.greaterEqual(from)

.lessEqual(to).build(); // from 06 July 2014 until today,

// both ends inclusive

IntegerInterval.builder().build(); // from negative infinity, to positive infinityOr you can use one of the constructors

public <T> Interval(T start, T end, Bounded type)

public <T> Interval(T value, Unbounded type)for example like this

new IntegerInterval(0, 2, Bounded.CLOSED_LEFT); // the interval [0, 2). The start point is inclusive, end point is not

new DoubleInterval(1d/3, 10.1, Bounded.OPEN) // the interval (0.333(3), 10.1)

new IntegerInterval(5, Unbounded.OPEN_RIGHT) // the interval (negative infinity, 5)

new IntegerInterval(3, Unbounded.CLOSED_LEFT) // the interval [3, positive infinity)If you need a special interval class, you can create your own subclass of the generic class Interval<T>. The majority of the methods from the interval arithmetic will be transferable and you don't have to overwrite them. The only abstract methods, that you do need to implement are:

public T getMidpoint() // returns the middle of the interval. This is needed for the tree.

protected Interval create() // returns a newly created instance of the class. Needed to avoid reflexion.The Interval class requires its generic type variable to implement the Comparable interface. Because of that, there are many interval methods, which will be available to your subclass out of the box. Please refer to the documentation of the Interval class for the full API. To illustrate some examples, here we will use the subclass IntegerInterval, since it is probably the most intuitive one:

IntegerInterval main = new IntergerInterval(0, 100, Bounded.CLOSED); // the interval [0, 100]

IntegerInterval next = new IntegerInterval(20, Unbounded.OPEN_RIGHT); // the interval (negative infinity, 20)

IntegerInterval small = new IntegerInterval(20, 80, Bounded.OPEN); // the interval (20, 80)

main.contains(50); // true

main.contains(-3); // false

main.contains(small) // true

small.contains(20); // false, end is open

main.intersects(next); // true

main.isLeftOf(200) // true

main.getIntersection(next); // returns the interval [0, 20)All intervals are represented by four class properties. start and end are instances of the generic type and represent the end points of the interval. There are also two boolean properties - isStartInclusive and isEndInclusive, which indicate if the corresponding end point is inclusive or exclusive. The interval classes are designed to be immutable, so you can't change the values of the four internal variables once you instantiate an object. You have access to them via getter methods, though.

Please note, that null values for the start and end properties are completely valid and represent negative and positive infinity, respectively. Please, consider that fact, if you extend the Interval class yourself and keep in mind that null is an acceptable value for these properties.

The Interval class provides its own implementation of the methods hashCode() and equals(), which are based on the four internal properties. If you introduce new properties into your subclasses, please make sure to overwrite the hashCode() and equals() methods and reuse the implementation in the superclass, especially if you are going to be using your subclasses in data structures such as HashMap or HashSet.